2 July 2019 | 5 min read

Riding the Asian Tigers

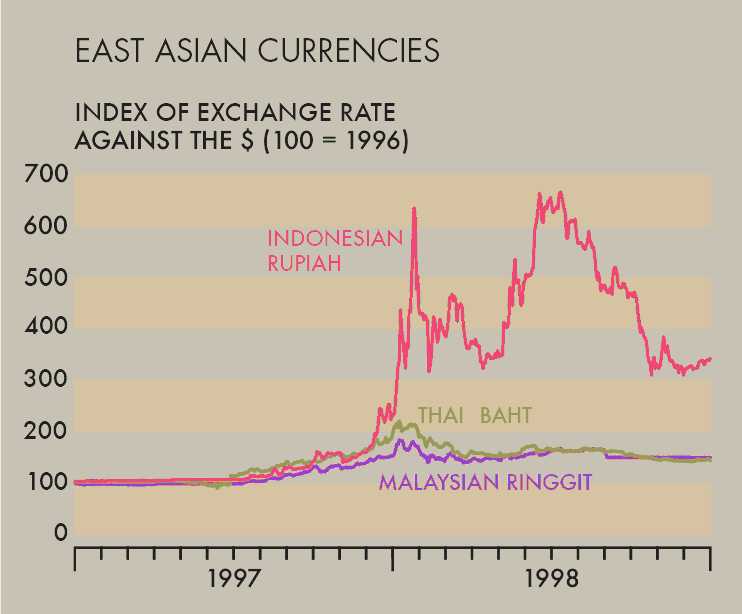

During the 1980s and the early to mid -1990s, the East Asian Tigers leapt ahead, fed on a rich diet of foreign capital. But in the wake of Mexico’s default (1994) and Japan’s banking crisis (1996), international investors began to regard Asia more warily and savagely attacked regional currencies one by one.

Massive and rapid growth is a wonderful buffer. Like a river in flood, it hides the rocks on the river bed.

Mahathir Mohamad, Malaysian Prime Minister

Easy Tiger

The rise of the Tiger Economies in the early 1990s was intimately tied to the after-effects of the Japanese asset bubble. Diminishing opportunities at home encouraged Japanese banks to ramp up their lending to other Asian countries – in particular to highly speculative real estate concerns – and by 1995 they were providing nearly half the credit of the region.

At the same time, falling Japanese interest rates led to the emergence of a carry trade in yen, where international speculators would borrow cheaply in yen and then invest in higher yielding regional currencies, such as the Thai baht, and earn the spread. Such arbitrage trades resulted in massive flows of hot money into countries such as Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia.

This deluge of easy money led to construction booms throughout the region, climaxing in mid-1997 with the completion of Kuala Lumpur’s Petronas towers.

During the early and mid-1990s, almost everywhere in East Asia had become a building site. Entire cities were transformed. For example, by the end of the decade Hanoi, which in 1992 had been a sleepy town of French colonial villas, swishing bicycles, with restaurants known by their street numbers, had metamorphosed into a sprawling, dynamic city.

As had been the case in Japan a decade earlier, real estate prices skyrocketed. Although the growth was based on a splurge of speculative credits, many Asians attributed the boom to strong fundamentals and their superior ‘Asian values’: diligence, respect for authority, the elevating of collective rights over individual rights.

They also believed that these same values would offer protection against the social and political pressures which have frequently accompanied periods of rapid growth in the West, allowing their boom to continue forever. In this way they were able to rationalise the prevailing euphoria.

Baht Out of Hell

The first clouds upon the horizon appeared in the wake of the 1994 Mexican Peso Crisis, which gave investors pause for thought about investing in emerging markets. The region’s troubles then intensified in mid-1996 when Japanese banks began repatriating capital from Asian countries, due to a domestic banking crisis.

These developments were particularly unwelcome for Thailand, which had been the primary beneficiary of the carry trade, and by early 1997, the Thai baht – pegged at B25 to the US dollar – was looking highly vulnerable.

Events gathered pace in early May, when Goldman Sachs released a research note predicting that the baht would soon undergo a competitive devaluation. A few days later, there was a speculative attack on the baht to which the Bank of Thailand (BoT) responded by calling for the intervention of regional central banks and creating a liquidity squeeze in the offshore market.

It did this by forbidding local banks to supply baht to foreigners, pushing up overnight lending rates to 1000–1500%. Hedge funds reportedly lost $300m. Then, on 2 July, BoT floated the baht which by the end of the day had lost 14–19% of its value, prompting the BoT to request IMF assistance.

The shockwaves of Thailand’s currency crisis spread throughout the region in what the Thai foreign minister termed the ‘Tom Yum Koong Syndrome’, referring to the famous Thai hot shrimp soup, which is ‘very spicy and dangerous for those who come unprepared’.

Speculative attention then turned towards the Philippines, whose central bank was forced to spend $540m in a single day on defending the currency.

Malaysia received the same treatment on 8 July and allowed the ringgit to depreciate (though did not require IMF assistance). Malaysia’s prime minister complained that his country had been targeted by a sinister Jewish conspiracy and singled out George Soros for particular blame, branding him a ‘moron’.

He also declared that currency trading was ‘unnecessary, unproductive and immoral’ and ‘should be stopped’, prompting Soros to retort the next day, ‘Dr Mahatir is a menace to his country’.

Let Them Eat Cake

The crisis then headed northwards to Hong Kong. Rising interest rates, due to pressure on the HK dollar, led to four consecutive days of massive losses at the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, coming to a head on Black Thursday, 23 October, when the HSI lost 10% and the Hong Kong Interbank Offer Rate reached 280%.

‘This is a full-fledged, absolute crash’, said one local analyst. Even America was beginning to wake up to the severity of the crisis and, on the same day, the DJIA lost over 7% (554 points) – its biggest ever one-day decline.

However, US investors were at the time in love with domestic internet stocks and quickly resumed bullishness.

Hong Kong was also forced to endure the blind terror of a ‘cake’ run, as thousands of people descended upon the Saint Honore Cake Shop to redeem coupons for future purchases. There was also a run on Whimsey Amusement arcades, where winners anxiously sought to exchange their tokens for soft toys before it was too late.

South Korea was next in the firing line. As the Asian Crisis intensified, foreign banks were increasingly refusing to roll over the debt of South Korea’s huge chaebol (manufacturing conglomerations) and by early November eight of these conglomerates were in deep trouble.

Later the same month, Seoul’s stock market crashed and the situation became so dire that on 3 December, Seoul was compelled to accept an IMF loan of $55bn. ‘Many Koreans consider that day to be South Korea’s “Second National Humiliation Day”, the first being that of the colonisation of the Japanese.’

The ‘humiliation’ of accepting help from the IMF was felt so deeply that Korean housewives donated their jewellery in order to help the government pay off its debt as quickly as possible.

Timorous Investors

Of all the countries involved in the crisis, Indonesia suffered most. Between 1996 and 1999, Indonesia’s stock market lost 76% of its capitalisation (35% of GDP).

Concerns over the state of the banking system and mounting inflation had led to capital flight: between July and December 1997 the Jakarta Composite Index had fallen by 45% and the rupiah by 55%.

The IMF was brought in to help, but President Suharto, sensing an attack on his authority, defied its demands for reform, and far from introducing the necessary austerity measures, swung to the other extreme and on 6 January announced an expansionary budget.

Following the announcement, the rupiah fell within two days from 7,500 against the US dollar to 10,000, and in the same week the JCI declined by 14%. ‘In a frenzy of panic buying, crowds in Jakarta had cleaned out all shops and supermarkets to get rid of their melting rupiah and to stock up.’

Ten days later there was another commotion, this time over the publication of a picture showing the IMF’s managing director standing like a schoolmaster over a subservient President Suharto, depicted signing the second Letter of Intent.

With this, ‘the aura of the invincible Hindu God King was broken’, and on the same day a group of military figures called for his replacement; he was eventually forced out of office in May amid widespread demonstrations.

After the extended crisis, the weary Tigers slumped in a heap on the floor: ‘In the Chinese calendar 1998 is the year of the tiger, but in this region, it is looking more like the year of the slug.’

Building work came to a halt all over East Asia, in particular in Thailand, where the crisis had originated. The Economist wrote of Bangkok, ‘The cranes are idle, and snazzy office and luxury apartment blocks stand empty. In Bangkok an urgently needed road and rail link between the airport and city centre has been abandoned half-finished, its concrete pillars reminiscent of Roman ruins.’

Goodbye Finance One

The following song was composed by Thai stockbrokers in September 1997 and is set to the music of Elton John’s ‘Candle in the Wind’.

Bre-X

Doing business in Asia during the boom was lucrative but risky, as the experiences of Bre-X, a small Canadian mining company, amply demonstrated. In February 1996, Bre-X’s geologists claimed to have made a massive gold discovery in Busang on Borneo, leading to a tenfold increase in its share price.

However, the company soon found itself up against the mining interests of President Suharto’s children and was forced to give up a large part of its claim in what has been described as a most ‘unedifying spectacle’.

It later transpired that the gold did not exist and that the ‘discovery’ had been made up by the geologists to manipulate Bre-X’s share price. One of the company’s two geologists had apparently committed suicide by jumping out of a helicopter and a body was later discovered in the jungle, but the body had been mutilated by wild pigs and therefore could not be positively identified.

The other geologist meanwhile had allegedly made millions selling Bre-X shares at an opportune moment and subsequently moved to the Cayman Islands to escape prosecution. As well as infuriating Bre-X’s shareholders, the affair was embarrassing for Suharto.