28 June 2017

Investment Catalysts: Palladium’s Inexhaustible Price Swings

Palladium – used in the catalytic converters prevalent in gasoline vehicles - has been this year’s best performing commodity, rising 30%. One reason: speculators betting that car owners will shun high-polluting diesel automobiles, which use platinum catalysts, and prefer palladium-fitted gasoline vehicles. As a result, the palladium price is poised for the first time in 16 years to overtake that of its supposedly superior sibling, platinum.

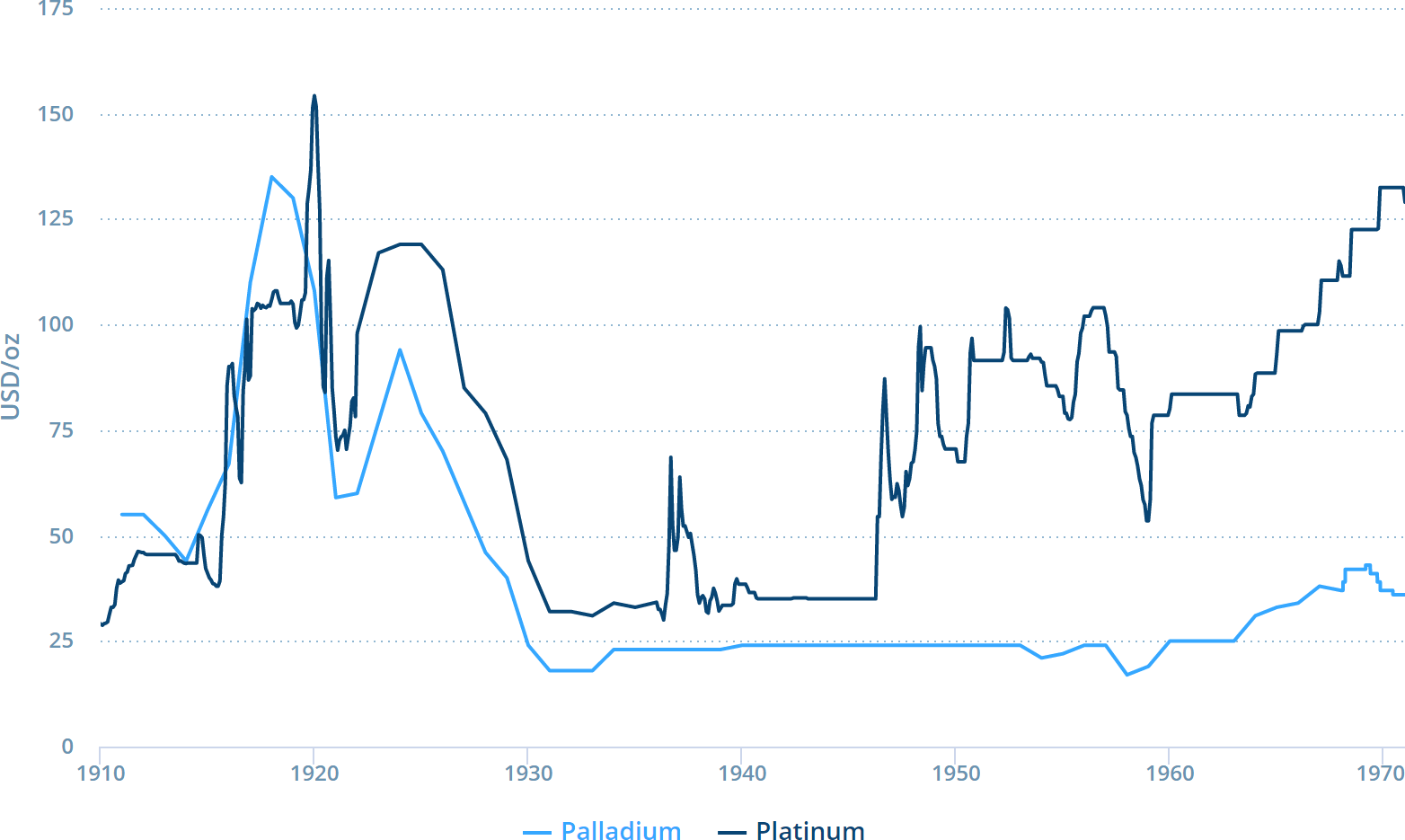

The palladium market is both thinly traded and sports minimal stocks, leaving it prone to big price swings. Booms and busts are evident in the long-run chart of the palladium price below, some of which have persisted for years, as this analysis reveals.

Palladium and Platinum Prices (1970-2017)

Indeed, the recent jump pales in comparison to the period from 1997 to 2001, when prices increased nine-fold, or during World War I, when they tripled. The historic volatility of the metal’s price has been compounded by the fact that production has been heavily concentrated in Siberia and thus linked closely to Russian political upheaval.

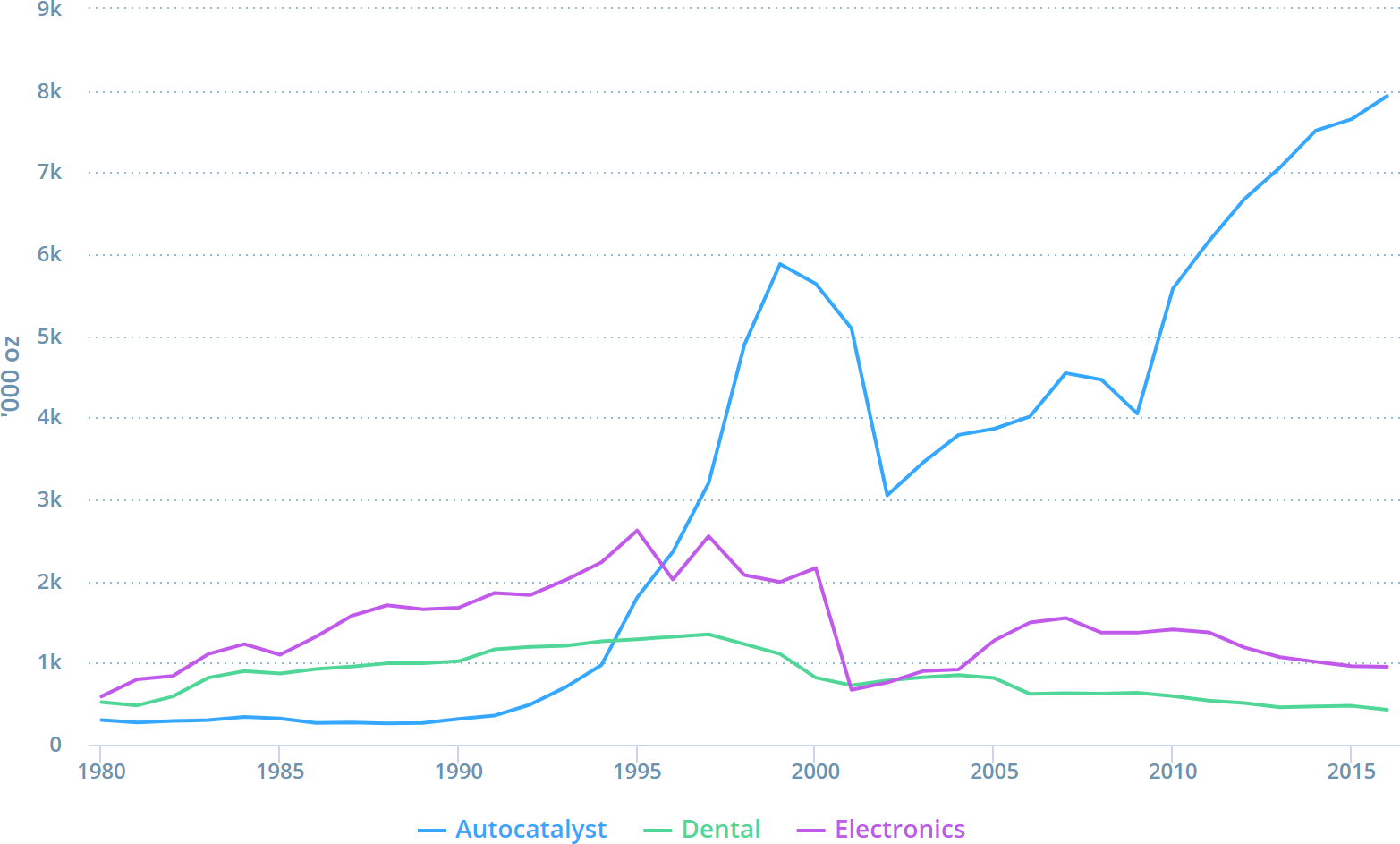

A steely-white metal, palladium was once exclusively used in industry, including in autocatalysis, jewellery, dentistry, electronics and the chemical industry. But in recent years it has become an investment vehicle. Similar dynamics affect platinum, which is sometimes assumed to be inherently more valuable than gold due to a range of cultural associations—from credit cards to anniversaries—quite apart from distinct fundamentals.

War Sparks Rise (1914-20)

During World War I, the need for explosives and engine spark plugs, which relied on palladium and platinum, caused the prices of both metals to surge. In 1914, Russia – responsible for 90% of the world’s platinum and palladium supply - banned the export of unrefined metal to encourage the development of domestic refineries. The Allies requisitioned their own stocks and prohibited exports to prevent reshipment to Germany.

Palladium and Platinum Prices (1910-1970)

Twin Peaks (1972-80)

The 1970s witnessed two distinct palladium booms, coinciding with the twin oil price shocks and rampant inflation. The 1975 Clean Air Act generated demand for platinum group metals, key ingredients in catalytic converters. Sharp price swings in palladium futures put considerable strain on the prevalent model of long-term contracts. Ultimately, most consumers and producers adopted market pricing, ushering in an era of greater volatility. And while the ascent of gold and silver during the 1980 precious metal boom was legendary, as oil producers and others sought refuge from the devaluing dollar, palladium fared even better.

Fusion Fever (1989-92)

Palladium boomed again in March 1989, when two professors from the University of Utah announced they had produced nuclear fusion at room temperature using a palladium cathode wrapped with platinum wire in a heavy water solution. To speculators, this heralded a cheap and clean method of power generation. Spot prices surged to $180 as investors piled into the market, prompting several companies to cash in on the frenzy by minting commemorative cold fusion medallions. Even the USSR joined the capitalist fray, issuing palladium coins honouring Christianity.

But the boom quickly collapsed when others failed to replicate the results. Prices sagged further as the US recession dampened demand, and the collapse of the USSR unleashed stockpiles onto world markets.

Palladium Prices (1988-1989)

From Palladium to ‘Unobtainium’ (1997-2001)

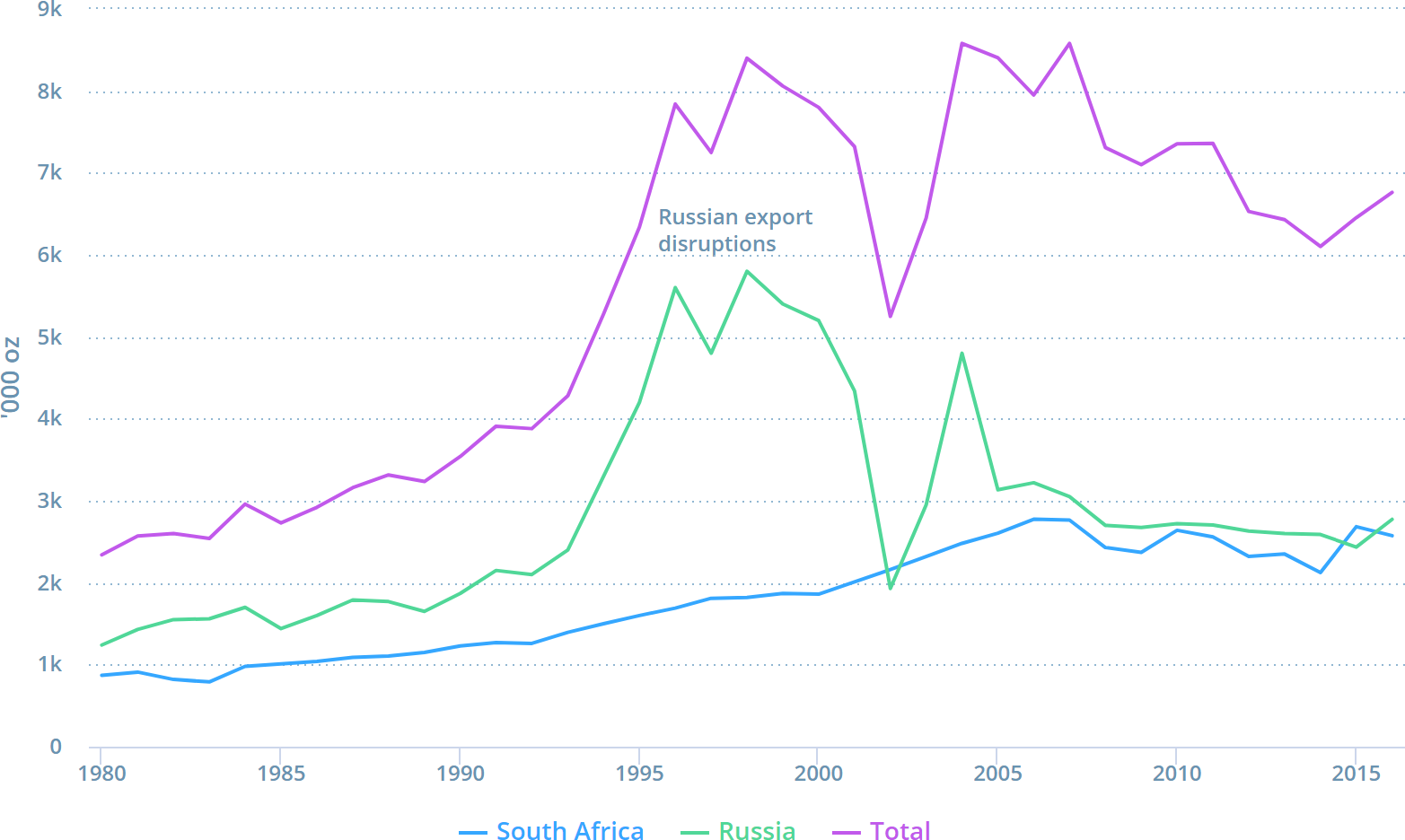

Palladium’s most spectacular boom took place in the late 1990s, driven by a surge in demand for catalytic converters. Automakers had preferred to use platinum, since it could handle the presence of lead and sulphur, but changes in fuel removed its advantage. Palladium was also more efficient at reducing hydrocarbon emissions and was significantly cheaper.

Meanwhile, Russian supplies were becoming less certain. Russia had traditionally used its stockpiles to stabilise the price, lulling consumers into a false sense of security. Unanticipated bureaucratic delays to shipments in 1997 and 1998 drove prices from $120 to $420, making it more valuable than gold and platinum. At the same time, Russian stockpiles were being depleted, but no one knew exactly how quickly, and bullish speculators drove the price to nearly $1100 in January 2001. This rising scarcity led one broker to dub it “unobtanium.” Hedge fund Tiger Management even offered to purchase Russia’s entire stock of precious metals during the 1998 financial crisis, and considered chartering an armoured train to transport the haul from Siberia to Switzerland. But the deal fell through after Russian officials demanded a “private commission”, as Sebastian Mallaby recounted in More Money Than God.

Palladium Demand

Trinkets and ETFs (2005-10)

With the palladium price now well below platinum, automakers switched back to using palladium for gasoline catalytic converters, and Chinese consumers increasingly bought jewellery made from it. Another demand driver was the introduction of precious metal ETFs in 2007. Against this expanding demand, there was a supply shock. In January 2008, platinum mines in South Africa were closed for five days after the state-run utility, Eskom, ran short of electrical-generating capacity. Fears of a supply shortage caused platinum, palladium and rhodium prices to soar. The resumption of mining, followed by the global economic downturn in 2008, caused their prices to crash. But they quickly rebounded, primarily due to an influx of investment via ETFs.

Palladium ETF Holdings

Palladium’s Trendiness

Irrespective of whether palladium continues its current bull run—significantly outperforming other precious metals this year (see chart below)--there is reason to believe that the metal will continue to trend in the future. Ideally, palladium producers would be able to anticipate demand far forward and adjust output accordingly, but this has rarely happened, leaving the door open for fundamental imbalances to run riot.

YTD Returns for Precious Metals

It has been suggested that electric vehicles will ultimately bring about the demise of the palladium market. Yet a host of new applications such as fuel cells are being developed that may compensate for any shortfall in demand, if consumers do shift from gasoline-powered to electric vehicles. In contrast to the searing heat found in catalytic converters, predicting supply and demand in the palladium market demands the coolest of heads in a world of ever-shifting substitute prices, cultural preferences, and production levels.