21 January 2019

Down on the farm

Although big generalised manias in financial instruments tend to receive the most press coverage, history is rife with speculative frenzies in specific agricultural commodities which, despite their smaller scale, have been just as ruinous for those involved. This section rounds up several such examples, ranging from the Merino mania of 1809–10 to the ostrich feather bubble of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Sheep Thrills

From 1809 to mid-1810, American farmer-speculators descended upon imported Spanish Merino sheep with lupine ferocity. Spanish Merinos were renowned as the finest wool sheep in the world, certainly far superior to the rather scraggy colonial breed, and were much in demand when America began manufacturing its own cloth.

At the height of the mania, some farmers sold their entire annual harvest to buy a single Merino, and a lamb that had been worth $100 in 1807 might sell for $1,000. In one Delaware county, Merinos were prized so highly that a tax was levied on every dog, to compensate farmers for sheep which had been killed by dogs. Legislation also stipulated that ‘dogs shall not enter the sheep walks, nor shall sheep enter the dog kennels. In either case, the invader shall be repelled by force of arms. Let them bite the dust.'

The bubble eventually burst in autumn 1810 when the chaos accompanying the Peninsular War in Spain resulted in uncontrolled exports of Merinos. Prices came crashing down – one man who had repeatedly refused $1,000 for his buck ended up selling it for $12. ‘Entire flocks of the finest Merino sheep’, wrote an observer, ‘were devoted to the knife, for no other reason but that, contrary to the wish and expectation of the owner, they would persist in eating!’

One speculator expressed his reversal of fortunes in verse:

When first Merino’s bless’d our land

Thro’ Humphreys’ patriotic hand,

Methought I’d be a patriot too

And buy a ram Merino true;

One hundred eagles was the price,

I paid the shiners in a trice;

I’ll risque my fame and fortune too,

Quoth I, on what a ram can do.

Scarce did my hobby ’gin to thrive,

’Ere thousand Spanish rams arrive,

And what I dream’d not of before,

My ram turned out to be a bore.

Mulberry Madness

‘Nature has never produced a more convincing demonstration of the triumph of life over death than these shabby, down-at-the-heel, despised old trees’, somebody once wrote of the mulberry tree. Yet at one stage speculators could not keep their hands off its wart-ridden skin, and were willing to pay fortunes for a single stump.

Mulberry trees are the natural habitat of silkworms and when several US states began subsidising their silk producers in 1832, the tree came into high demand. Huge plantations containing hundreds of trees sprang up all over the country.

By 1838, however, it was clear that the massive premiums being paid for the trees could in no way be justified by the underlying demand and the mulberry mania came crashing down. One contemporary wrote that the mulberry speculation had ‘fallen suddenly like a tremendous Colossus, and it now lies sprawling with a good many under it who are crushed by its fall.’

Storm in a Teacup

When British tea traders were hoofed out of China in 1839, they turned their gaze to the Indian province of Assam as a potential tea growing area. A company was quickly set up and over the next two decades increasingly large areas of Assam fell under cultivation, though growth was constrained by labour shortages.

The Assamese were ‘singularly disinclined’ to work on the farms, whilst imported Chinese workers turned out to be ‘turbulent, obstinate and rapacious’ and were promptly dismissed. In fact, most of the work ended up being done by elephants.

In 1861, new land ownership laws and the importation of cheap labour (‘Coolies’) from South India touched off a mania known as the Tea Rush. ‘A madness comparable in intensity with that of the South Sea Bubble seized men’s minds, and normally level-headed financiers and speculators began to scramble wildly for tea shares and tea lands.’ Frauds abounded. Promoters often lumped together good gardens with useless tracts of jungle, selling the whole lot to London-based companies for several times the actual value.

Whilst investors were making big gains, the workers who generated their profits faced abominable conditions. ‘They die very easily’, coolly noted one British observer, as if describing a genetic flaw. They lived in closely guarded areas known as ‘Coolie lines’, and ‘savage’ hillmen were employed to track down deserters with specially trained dogs. When they were caught, they were subjected to a severe flogging and the captor’s reward was deducted from their future earnings.

‘The stick has a greater terror for those innate thieves and scamps for whom flogging is useful; the quiet, firm systematic way the government floggings are conducted.’

Eventually, by 1865, many of those who had bought up tea shares and tea gardens a few years earlier realised that they were never going to make the level of profits that they had been expecting and sold their investments en masse, sending share and land prices crashing. There were further declines the following year, reflecting the dismal quality of Assamese tea at the time, and it was not for another decade that India began exporting good quality tea at a profit.

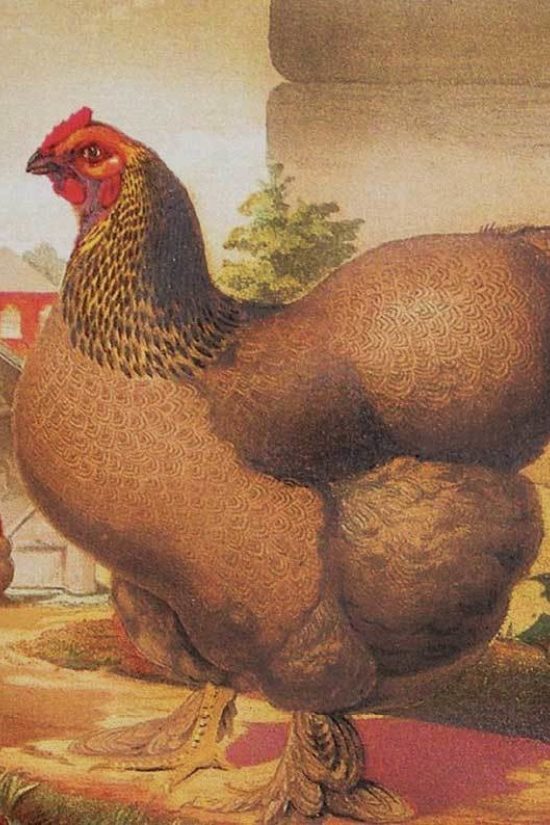

Fowl Play

In 1852, the exotic Cochin chicken from China became a must-have item, with The Times observing, ‘just now nothing seems so irresistibly attractive as a large gawky fowl without a tail.’ Everybody was awestruck by the colossal size of the new birds: ‘the Cochins came like giants upon the scene; they were seen, and they conquered. The few people who were first tempted to the shows went home and told with wonder that they had seen fowls as large as ostriches which nearly blew the roof off with their awful crow; or roared like the lions in the Zoological Gardens.’

As was the case with tulips two centuries earlier, investors were not concerned with considerations of underlying utility, such as meat quality, egg laying capacity or things of that kind. In fact, Cochin fowls were actually rather poor specimens, one paper describing them as ‘subjects for the Foundling Hospital in their semi-nudity’.

Yet for many owners this did not detract from their charms. Some doting owners knitted polka jackets for them. Poultry associations were set up all over the country, and a highly specialised literature emerged.

Wright’s Illustrated Guide to Poultry, for example, contains features ranging from new French contraptions for force-feeding capons to a schema of an aristocratic lady’s poultry yard. Ultimately, however, values slumped and investors were left with egg on their faces.

Poultry mania also swept the US, making its debut at a massive Boston show in 1849 which drew thousands of spectators. Americans, like their British cousins, were just as impressed by the newly imported fowl. An ex-Congressman was even able to maintain a straight face when declaring that ‘next to a beautiful woman and an honest farmer, I deem a Shanghai cock the noblest work of God.’

Hare-Brained Pursuits

In 1872 and 1873, Tokyo was bouncing up and down with bunny mania. During the 1868 Meiji Revolution, Japan’s warrior class – the Samurai – were disbanded and suddenly had nowhere to go. Fortunately, they received some compensation and were told to look for investment opportunities, which came bounding onto the scene in the form of fluffy bunnies imported from Europe. These rabbits gained immediate popularity amongst Japan’s élite.

Monthly auctions were set up in the summer of 1872 and prices quickly rose, massive premiums being paid for rabbits with rare features such as yellow ears. Rabbits routinely changed hands for several hundred yen and one particularly valuable rabbit was sold for 600 yen at a time when the average monthly wage was only 0.57 yen. Indeed, such was the speculative frenzy that some people were prepared to exchange their daughters for rabbits and one young man killed his father for refusing an

offer of $150 for their rabbit, which died soon after.

Alarmed at these extremes, Tokyo’s governor prohibited rabbit auctions in early 1873, but his jurisdiction did not extend to the city’s foreign merchants, who were able to organise their own auctions. Pondering how to arrest the on-going speculation, he later introduced a ‘rabbit’ tax of 1 yen a month. The bubble was immediately pricked and prices slumped to 0.2 yen (compared with an average of several hundred before the tax). Many owners stole into the woods at night and released their four-legged investments, whilst others put them in the hotpot or flayed them for their fur.

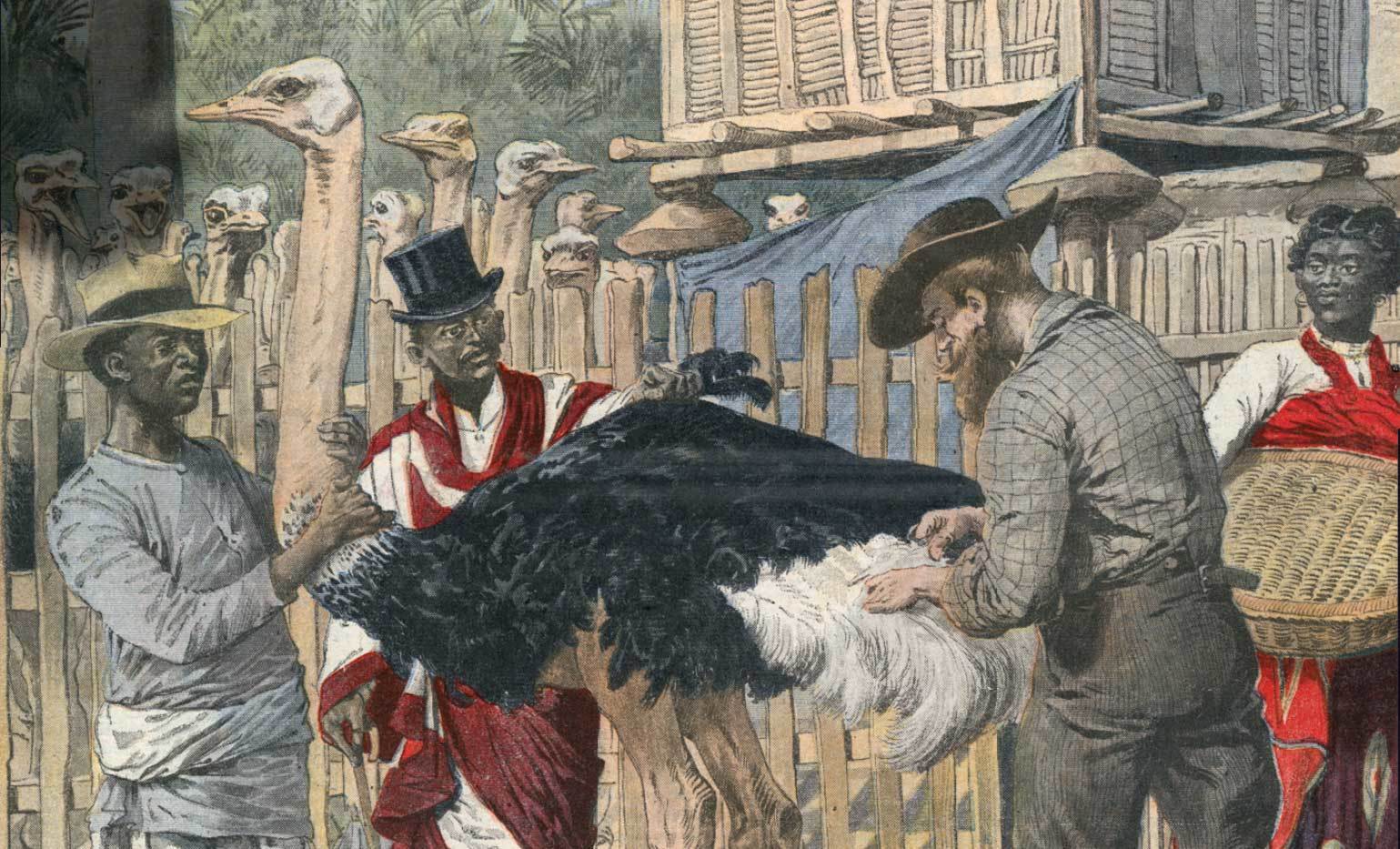

Plume Crazy

Ostrich feathers took off in a big way in the 1880s. ‘A well-dressed woman nowadays is as fluffy as a downy bird fresh from the nest’; ‘If you would be fashionable this winter, you will be beplumed.’ Soaring international demand encouraged South African farmers to rear more birds and by 1913 the ostrich population of Little Karoo (the region at the heart of feather mania) grew from practically nil to 776,000.

South African farmers and feather merchants became extremely wealthy on the back of the trade and started building ostentatious feather mansions which boasted ‘panelled walls, tiled bathrooms, hand-painted friezes; the finest mahogany, walnut, and oak furniture... gilt concave mirrors, silver and Sheffield plate, the best Irish linen.’

At the market’s height in 1913, farmers were expanding, and brokers and investors were stockpiling large quantities of feathers in anticipation of even higher prices. Many in the trade were utterly convinced that the profits would keep rolling in, for feathers, like diamonds, were an ‘investment for life’, and in 1911 the world’s only ostrich professor confidently stated that ostrich farming would be a permanent feature of South African farming.

Three years later, however, the feather market began a precipitous and permanent decline. By late 1914, changing fashions, growing concerns over animal cruelty and conservation and the advent of the motor car, which rendered elaborate headgear impractical, all spelt the end for feather mania. The crash resulted in great hardship for South Africa’s feather farmers and merchants.

Scores of farmers committed suicide rather than face life without their farms. Merchants’ feather mansions were auctioned off for the price of their windows and doors – one merchant even forced his wife to sell her oven door to pay off his debts. Ostrich carcasses littered the South African landscape because farmers could not afford the birds’ feed.