1 October 2018 | 6 min read

In Quest of Aztec Gold

Armed with cheap banknotes and a romantic disposition, British speculators ventured deep into the jungle of Latin American investments during the early 1820s in the quest for the continent’s legendary treasure mines. Yet all they found were profit-sucking leeches and accursed pyramid schemes .

Tropical Delight

After the Napoleonic Wars, the British government and Bank of England followed deflationary economic policies to restore the convertibility of Bank of England banknotes to gold at pre-war (1797) levels.

Parliament passed the Resumption Act in 1819 and the convertibility of BoE notes resumed in 1821, but country banks continued to issue unbacked paper notes. This surplus of cheap, unbacked credit fuelled domestic speculative investments in Latin American sovereign debt and mining stocks, and domestic joint-stock companies.

Nathan Rothschild

Nathan Rothschild, born in Frankfurt in 1776, emigrated to England in 1799 and spent the first ten years exporting textiles back to Germany. In 1809 he moved into banking and wholeheartedly dedicated himself to his new career, claiming ‘I do not read books, I do not play cards, I do not go to the theatre, my only pleasure is business.’

His big break came in 1815 when he was commissioned by the British government to help finance the renewed war effort against Napoleon, though this very nearly proved his undoing.

Anticipating a lengthy war, Rothschild had supplied Wellington’s forces on the Continent with vast quantities of gold for the purpose of buying provisions. So when Wellington vanquished Napoleon at Waterloo, ending the war sooner than had been expected, Rothschild’s gold became redundant and started to decline in value.

Facing ruin, Rothschild took a desperate gamble by staking all the gold on a rise in Consols. The gamble paid off, allowing Rothschild to establish a bank and set himself up as a dominant player in London’s increasingly international bond market.

After gaining independence from Spain, several South American nations, starting with Colombia, issued bonds in March 1822. These became very popular amongst British investors as they paid much higher rates on interest than British government Consols and were issued at steep discounts. However, many of these issues were Ponzi schemes, whose proceeds went primarily to British ‘contractors’ with what remained often being frittered away on fighting wars with neighbouring countries.

Moreover, investors found it difficult to distinguish the more trustworthy issuers, so all the issues were similarly priced at punitively low levels. This meant that the market was dominated by low quality sovereign issuers such as Peru, rather than higher quality issuers such as Brazil which could resort to internal sources of funds or borrow more cheaply from a narrower group of knowledgeable investors.

Indeed, there was such little information on the issuers that in 1822 a fictitious country called Poyais was able to float a loan successfully on the London market, priced at almost the same level as the issues of real countries such as Chile and Colombia.

A Royal Stitch Up

The Scottish adventurer Gregor MacGregor set himself up as the leader of a small, fictitious territory called Poyais (modern-day Nicaragua). His Highness MacGregor visited London in early 1821, intending to sell land rights and titles of nobility and encourage emigration to his country.

Finding a growing appetite for foreign loans, MacGregor arranged to float a £600,000 Poyaisian loan with a 6% coupon. The issue was a tremendous success, and the bonds sold at a hefty premium. In early 1823, 200 colonists arrived in St Joseph, the Poyaisian capital. Instead of the promised grand Baroque city, they found a malarial swamp surrounded by belligerent Indians. Only 50 colonists got back to Britain. MacGregor, meanwhile, fled to France with his family and the proceeds of the bond issue.

Montezuma's Mines

From 1824, there was also a boom in the securities of Latin American gold and silver mines. Investors were sanguine about what the application of British capital and mining expertise in these newly established countries could achieve, believing they had not been developed to their full potential under the Spanish, and were tickled pink by the claims of company prospectuses that neglected gold nuggets could be found lying everywhere.

Investors were also animated by a sense of the romance of those far-off lands; ‘When the grey haired merchant grew eloquent by his fireside about the clefts of Cordillera, where the precious metals glitter to the miner’s torch, it was not his expected gains alone that fired the eye’.

Britain’s recognition of the independence of Mexico, Buenos Aires and Colombia on 31 December took the mining boom to a new level. Writers were commissioned by mining companies to pen pamphlets which lavished praise upon their respective mines.

One of the most prolific pamphleteers was the future Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, who confidently proclaimed on April Fools’ Day 1825 that ‘an immense and permanent rise is to be looked to’ in the mining market. By that time, however, mining stocks had become dangerously overvalued.

It was not only capital that was sent to South America. The mining boom was also accompanied by an export boom as British merchants sought to break into the new South American markets; but supply far exceeded demand and British goods were left to rot on Rio de Janeiro’s beaches.

Many exports were also completely inappropriate for their intended markets: ‘It is positively declared, that warming-pans from Birmingham were among the articles exposed under the burning sun of that sky; and that skates from Sheffield were offered to people who had never heard of ice.’

Vampire Bats

For those unwilling to get involved with South American investments, there were also exciting opportunities at home and, following Nathan Rothschild’s successful flotation of Alliance Fire and Insurance Company in March 1824, there was a proliferation in domestic joint-stock company promotions as other entrepreneurs sought to emulate his success.

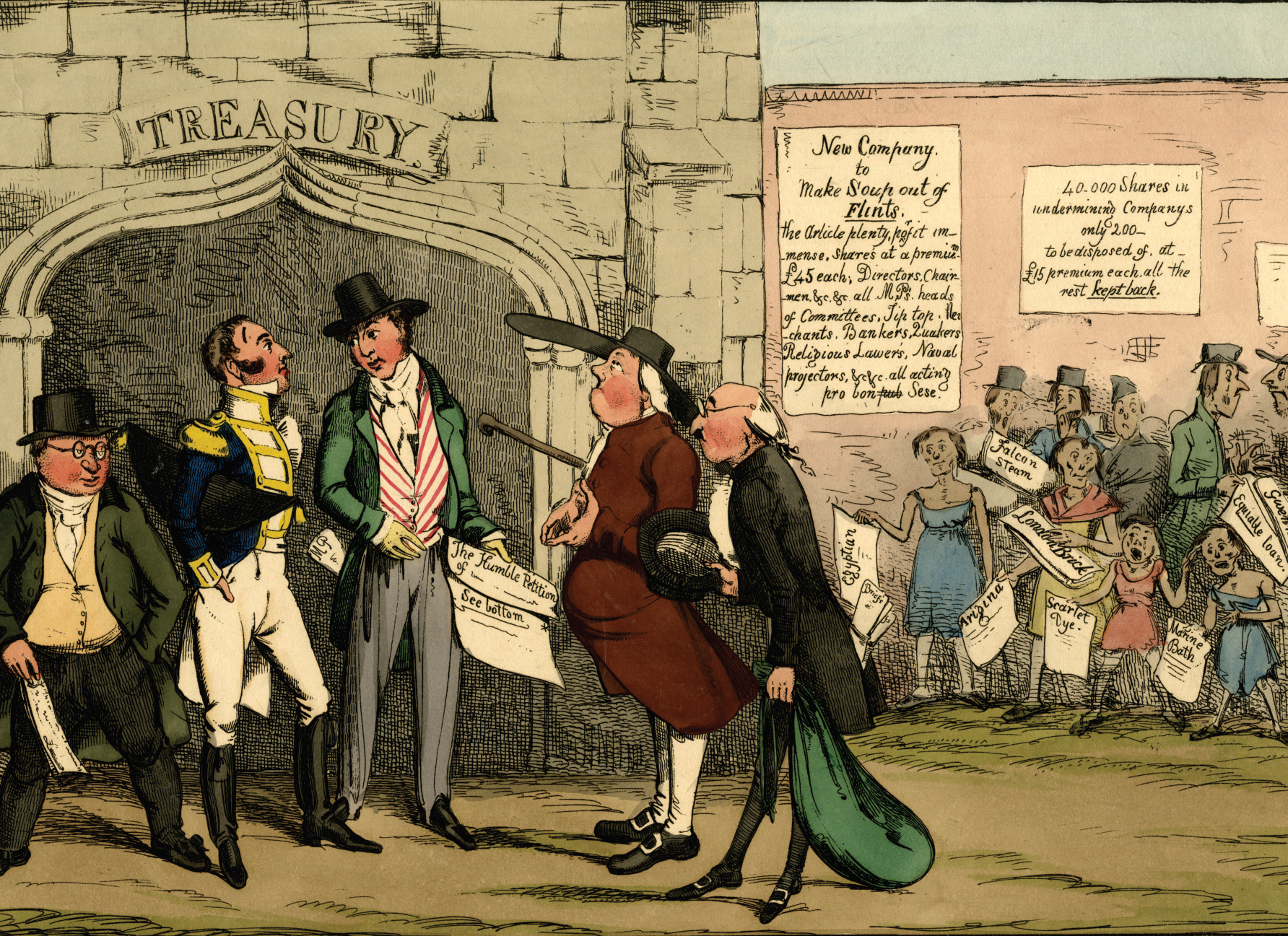

From this time ‘bubble schemes came out in shoals like herring from the Polar Seas’, illustrated by the fact that the number of bills coming before Parliament for forming new companies shot up from 30 in March to 250 in April.

All manner of companies were floated. Many were related to Assurance; there were also some novel ventures such as the Metropolitan Bath Company which aimed to pump seawater to London so that poor Londoners could experience seawater bathing, and the London Umbrella Company which intended to set up umbrella stations all over the capital.

Many ventures, however, were arrant swindles designed to test investor credulity. Such examples include the Resurrection Metal Company, which intended to salvage underwater cannonballs that had been used at Trafalgar and other naval battles, and a company (possibly a parody) which was set up ‘to drain the Red Sea, in search of the gold and jewels left by the Egyptians, in their passage after the Israelites.’

Parliament did little to restrain the speculative excesses of 1824 and early 1825, not least because many of its members had stakes in various mining companies and bubble schemes. Even the Chancellor, whose job it was to be concerned about threats to the economy, was sufficiently unconcerned to declare in his Budgetary Speech in early 1825 that ‘We may safely venture to contemplate with instructive admiration the harmony of its proportion and the solidity of its basis.’

Apart from complacency and inaction, the lack of an official response was partly due to the government’s concern that the ‘remedy would be worse than the disease, if, in putting a stop to this evil [i.e. speculation], they put a stop to the spirit of free enterprise.’

A handful of public figures including the Prime Minister and the prominent banker Alexander Baring did give the alarm, though to little effect.

Curse of the Golden Idol

Then, for reasons which are not entirely clear but may relate to the Bank of England’s decision to raise interest rates in April 1825, Real del Monte Mining Co. – the leading South American miner – buckled. Its share price plummeted from £1,550 on April 1825 to £200 by the summer, presaging a major stock market crash in London.

In the following weeks, other mining stocks fell and new flotations failed. The most spectacular decline was that of the Bolivar Mining Association, whose shares fell from £28 to £1.

Information on South American sovereign issuers had also improved markedly in the preceding months, leading to a sharp decline in the prices of lower quality sovereign debt issues.

By now, a major financial crisis was imminent. Alarmed at the amount of unbacked money issued by private banks, the Bank of England decided in August 1825 to rein in lending and beef up its gold reserves – which had declined to only 20% of the value of its banknotes in circulation – by raising interest rates still further.

It refused to discount even Baring and Rothschild notes. These credit contractions, combined with the regular seasonal tightness caused by tax remittances from country banks to London, led to a spate of country bank failures in September, October and November.

Learning From Misadventure

Despite the immediate pain suffered by many investors and the collapse of numerous firms, the Panic of 1825 was beneficial for the British economy.

The policy reforms made in the wake of the crisis made the economy more flexible and less vulnerable to exogenous shocks, and laid the basis for Britain’s dominance of international finance until WWI.

In July 1826, joint stock banks were allowed to establish branches throughout the country, rather than relying on correspondent country banks. This made the bills market more efficient and allowed banks to monitor their operations more effectively.

British commerce also benefited from the overhaul of the tax system, the repeal of the Bubble Act and the rewriting of the Bankruptcy Laws in 1831.

More importantly, the Bank of England learnt for the first time how to act as a lender of last resort.

Thanks to these factors, the national funded debt declined for the rest of the century (except in 1827) and the British government enjoyed the lowest borrowing costs of any European government throughout the 19th century, allowing it to mobilise resources and wage its wars more cheaply.

Caught in the Quicksand

The next stage of the crisis was much more dramatic. On 13 December, the London bank Pole, Thornton & Co. collapsed, dragging down forty correspondent country banks with it.

This time the Bank of England itself came under threat and sought to suspend convertibility to protect its almost empty gold reserves. As a strong supporter of free trade, the Prime Minister did not allow this but permitted the bank to raise its discount rate to the legal maximum of 5% and to issue a previously undiscovered stock of £1 notes which had been in an old vault.

These measures provided immediate relief but only a large infusion of gold (300,000 gold sovereigns) from the Banque de France in February, brokered by Nathan Rothschild, saved the bank and averted the suspension of convertibility.

However, this gold loan came too late for many country banks and firms. The previous autumn’s wave of bankruptcies continued into 1826, reaching a peak in April, by which time 73 of England’s 770 country banks had failed.

Many of the companies established in the sanguine days of 1824 and early 1825 disappeared. 624 companies were floated in 1824 and 1825, with a capitalisation of £372m. By 1827, only 127 of these remained, with a capitalisation of £100m but a market value of only £9m.

The History of Samuel Titmarsh

In Thackeray’s The History of Samuel Titmarsh and the Great Hoggarty Diamond (1841), Samuel Titmarsh is a clerk at the West Diddlesex Fire & Life Insurance Company, which had been established during the 1825 boom by Mr Brough.

Mr Brough is a successful turkey trader but has become involved in foreign government debt and domestic company promotion, puffing concerns as varied as The Ginger Beer Company, The Patent Pump Company and The Consolidated Baffin’s Bay Muff and Tippet Company in addition to the Diddlesex Company.

Initially, these speculations pay off and Mr Brough becomes one of the richest men in London, regaling ‘the great people of the land at his villa in Fulham’. Soon, however, the Diddlesex begins experiencing difficulties after the death of some of its policyholders and the loss by fire of some assured buildings.

‘Life insurance companies go on excellently for a year or two after their establishment, but... it is much more difficult to make them profitable when the assured parties begin to die.’ Eventually the Diddlesex collapses and Mr Brough escapes to France, taking a million pounds with him and leaving Samuel to face the music.

Samuel becomes bankrupt and is sent to a debtors’ prison but is rescued by his family, whilst Mr Brough is tracked down and loses everything, having to sell all his possessions to pay his creditors.

The moral of the story is that the City is a rewarding place for hard workers such those engaged in trade but punishes speculators (promoters and investors).