24 October 2018

From US Steel to URLs: what’s in a company name?

Companies choose their identities for many reasons. But are there patterns in the naming of corporations that could shed light on other financial market trends?

A corporate name change can occur for a variety of reasons, from companies’ desire to distance themselves from scandal or modernise their brands, to the reflection of a merger or acquisition or changing lines of business.

Some of the biggest US-listed corporations have simplified their names in recent years, in part at least to signal new ambitions. Apple dropped the “Computer” from its name when it announced the iPhone in 2007. More recently, Tesla Motors became Tesla. Similarly, Wal-Mart Stores switched to Walmart at the start of this year to reflect its commitment to online retail, and Weight Watchers announced in September that it would call itself WW to reflect its desire to be known as a diversified wellness business.

Some changes veer towards absurdity – or worse. Mondelez International, formerly Kraft Foods, unwittingly echoed vulgar Russian slang. The Tribune Publishing Company’s short-lived rebrand as tronc – short for Tribune Online Content – was mocked as “the sound of a millennial falling down the stairs”.

Names are one of many attributes of firms that can be quantified and analysed. Their associations - whether with corporate ambition or embarrassing misadventure - suggest that they could hold important information.

The Name Game

Because they are used to signal to investors, corporate names can be linked to financial market trends. This becomes most obvious during waves of technological optimism.

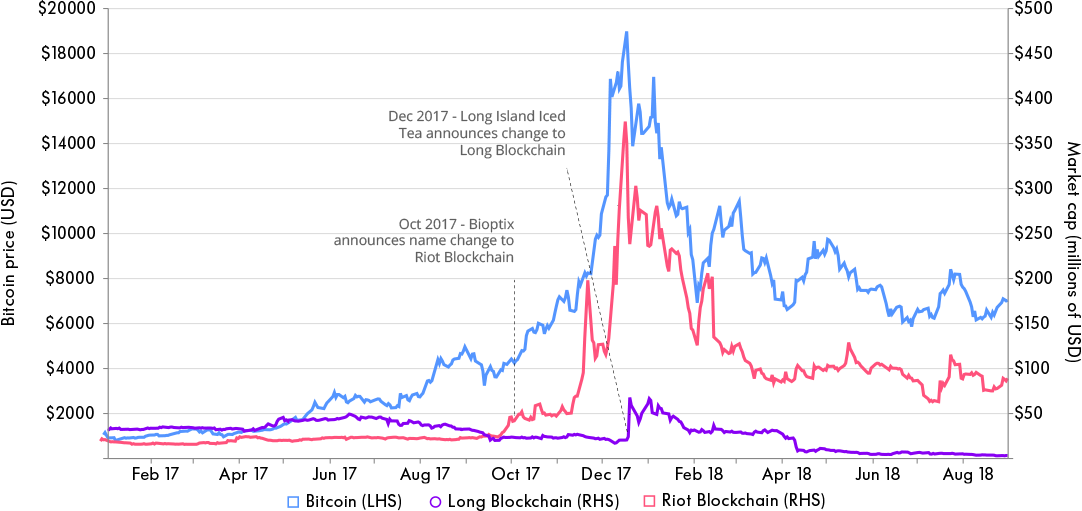

Blockchain is among the latest in a long line of hyped new technologies, and disparate firms have included it in their names in an attempt to cash in on the euphoria. Bioptix, a laboratory machine manufacturer, renamed itself Riot Blockchain as the Bitcoin price approached $6,000. The market cap of the company soared from $20m before the change to nearly $400m when the price of Bitcoin hit a peak in December 2017.

Around the same time, a drinks producer based in Hicksville, New York named Long Island Iced Tea rebranded as Long Blockchain. A stretch perhaps, but this switch also prompted a share price surge, with the company’s market cap trebling to almost $70m overnight.

The Soaring Valuation of Blockchain-Named Firms in Late 2017

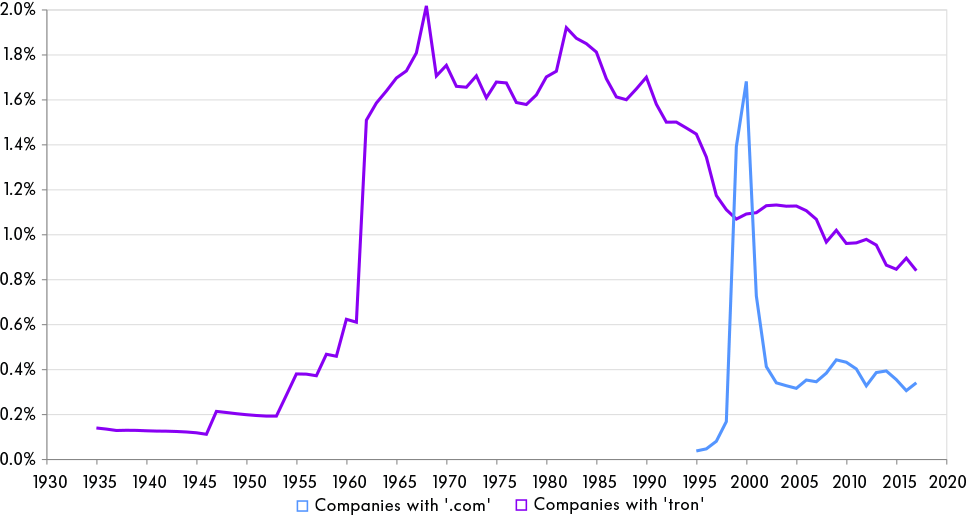

The cryptocurrency craze has echoed previous tech euphorias, such as the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s and the ‘tronics boom of the early 1960s. Excitement over the 1957 launch of the Sputnik 1 satellite was followed by the emergence of a fleet of space-age company names.

Share of US-Listed Companies with ‘tron’ or ‘.com’ in Name

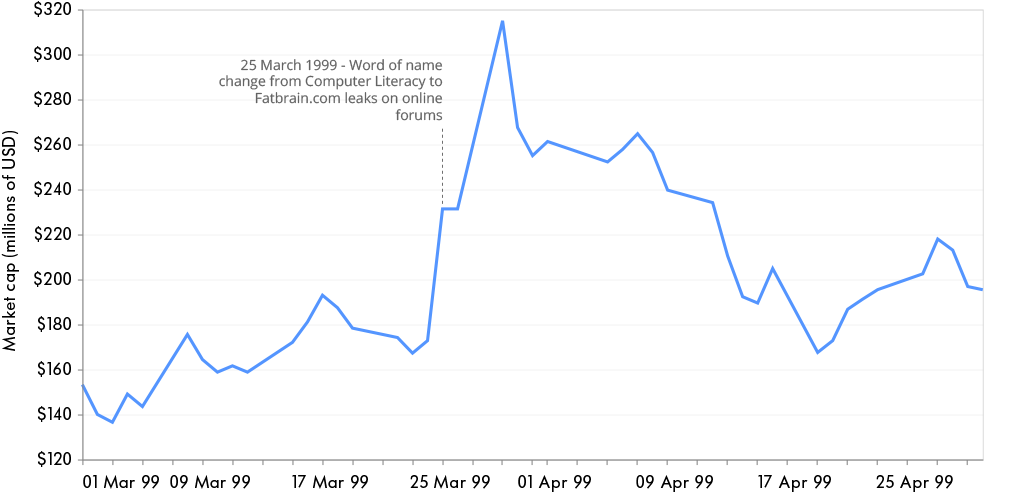

Similarly, during the tech boom at the turn of the millennium, firms rushed to adopt .com names. A case in point was Computer Literacy, a technical books vendor. Executives thought the name was dull, ugly and made for an awkward URL. Its management spent six months brainstorming before coming up with “Fatbrain.com”, along with the accompanying tagline: “Great minds think a lot”. The share price doubled as word of the change leaked, only to drift lower in subsequent weeks.

Computer Literacy / Fatbrain.com Market Cap

Dotcom Duds

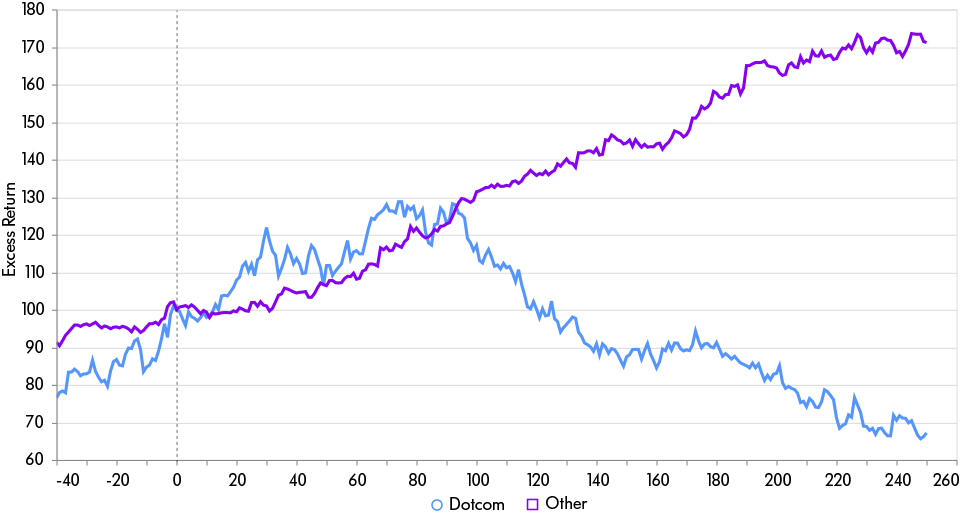

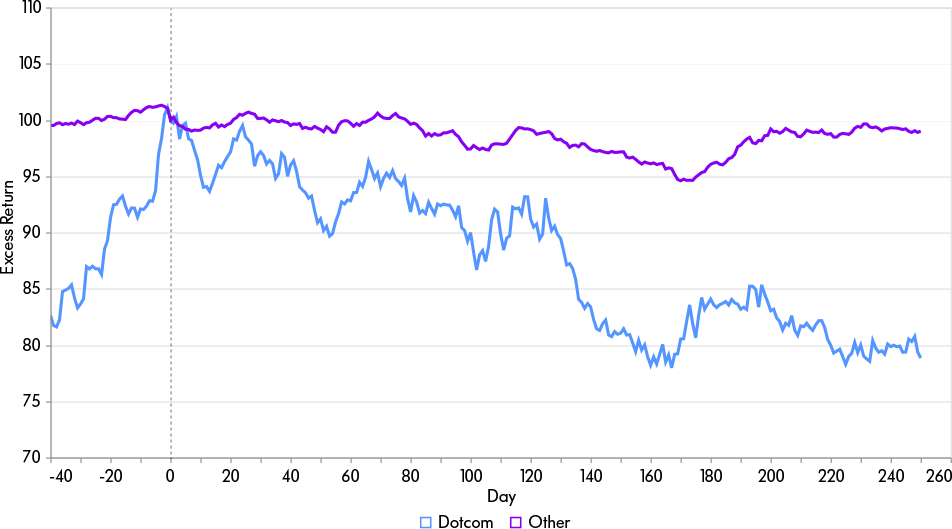

Market observers often cite stories such as Fatbrain.com’s as key exemplars of the dotcom bubble. But how did the eponymous firms actually perform? The following chart shows the mean excess returns for tech companies that changed their name to a .com name as well as those for tech companies that changed their name to a non-.com name between 1997 and 2001. The pattern is striking for .com firms, with an increase leading up to the official change and sharp underperformance that begins a few months after the switch. By contrast, tech companies changing their names to non-.com names outperformed the market by 70% in the subsequent year.

Mean Excess Returns of Name-Changing Tech Firms in Year After Event, 1997-2001

Looking at the broader universe of all companies changing their names in this period, firms changing to a .com name enjoyed outperformance in the run-up to the change and lagged the market subsequently.

Mean Excess Returns of All Name-Changing Firms in Year After Event, 1997-2001

Abstract Expressionism

Firms adopting .com names during the tech bubble do seem to have elicited excitement followed by disappointment – a testament to the potential power of names in markets. Another striking aspect of the history of company names is the dramatic change in their content over time.

The 1920s bull market was exciting in every respect except the names of the stocks being traded. Back then, it was easy to tell what companies sold from their names, which tended to include some combination of geographical references, founder names, product descriptions and common adjectives such as “general” and “standard”.

Unicorns in Black and White - Firms Worth Over $1bn in September 1929

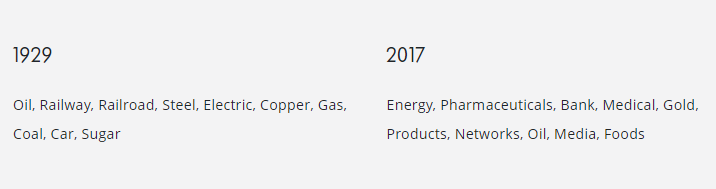

More literal company names have faded from view. Of the 10 largest US listings, only Bank of America’s name clearly states its function. Has this trend toward abstraction held more broadly? One way to quantify this is to compare company names to the UN’s export product code.

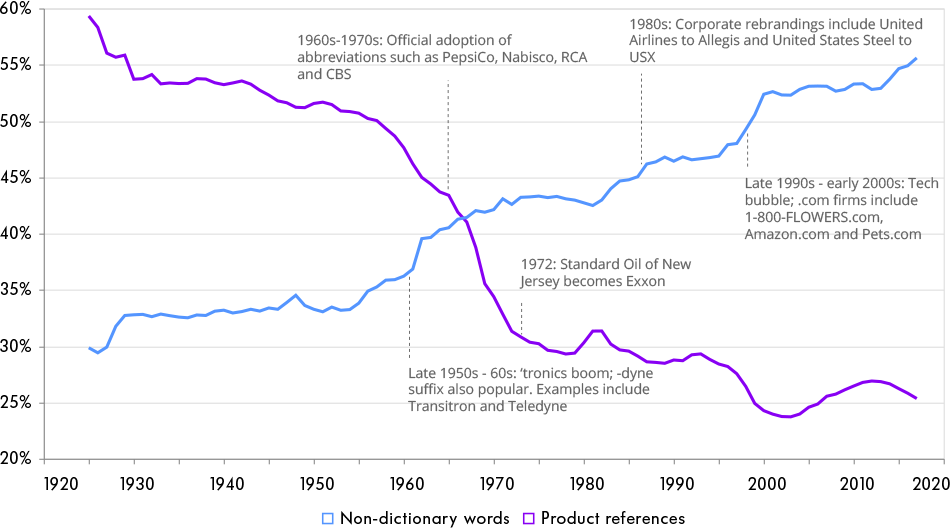

Share of US Listed Companies Using Product References and Non-Dictionary Words

The share of firms with names containing a word in that corpus has fallen from 60% at the beginning of our sample to under 30% today. The rising importance of services probably explains part of this decline. The changing nature of the economy is highlighted by the most common product references that do appear today, populated as they are by financial, medical and communications services.

Then and Now – Most Common Product References in US Company Names

Another contributor to the decline of product references is the explosive growth of neologisms in company names, which began around the middle of the 20th century. The share of firms with names using words not appearing in an English language dictionary – such as proper names and neologisms – grew from 30% in the 1920s to 55% today.

The initial onslaught of neologisms arrived around the time of the ‘tronics boom with names like Conductron, Itek and Teledyne. Many of these names would sound dated today. But firms continue to coin new words and expressions. A recent fashion involves adopting Greek- and Latin-influenced words without the retro-futuristic baggage of ‘tron’, ‘dyne’ and the like. High-profile examples include Verizon, Altria and Equinor. These have the advantage of being search engine-friendly and easy to pronounce across borders.

Other kinds of fashions have proved equally persistent. Since the 1960s, firms have increasingly turned their names into contractions or acronyms – examples include PepsiCo, Nabisco, RCA, AMF and CBS. In vogue currently are single-word names such as Alphabet, Apple, Snap, Square and Twitter.

Such minimalism is a far cry from the long, literal names that were once common. The shifting patterns in identities reflect changes both in commercial preferences and economic conditions. Studying the names of companies – one of their many fundamental attributes – offers a rich, alternative perspective on how equity markets evolve.