24 October 2018

The history of the modern international monetary system

Crypto-currencies such as bitcoin may be commonly associated with gunrunning and other illicit activities, but they nevertheless represent an attempt to reinvent the international monetary system in a more egalitarian fashion. They give power to people and according to their progenitors provide a digital analogue to gold – a claim which should perhaps be taken seriously given that they now command a similar price to gold. This feature traces the history of the international monetary system from the rise of the gold standard to the present.

The Contemporary Order

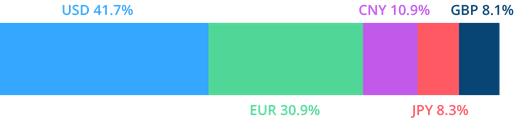

Before plunging headlong into 19th century history, we’ll briefly survey the current monetary order. The dollar remains the most important reserve currency by a long chalk. Most of the world’s developed nations possess floating currencies or form part of the Eurozone, whilst the currencies of developing nations tend to be pegged to the dollar (Asia, Middle East, South America) or the Euro (West and Central Africa).

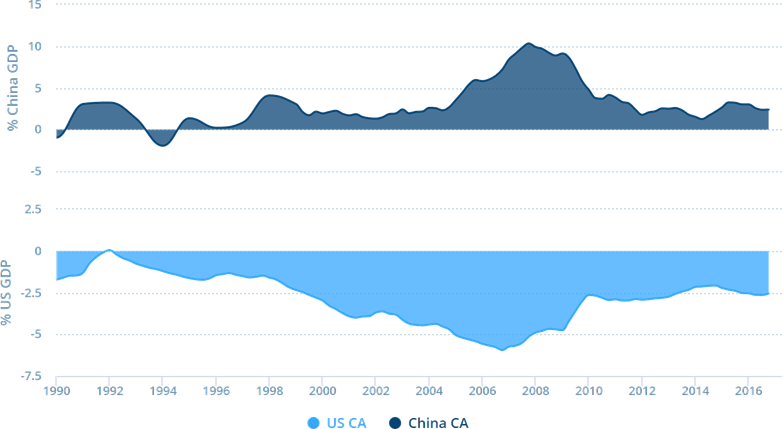

The absence of a systemic anchor such as gold and a supranational fiscal authority, has allowed various nations (notably China) to run chronic current account surpluses and others (notably the US) to run chronic deficits. This has led to the peculiar situation of the world’s poorest countries subsidising the lifestyles of the richest, and allowing the latter to assume gargantuan debt burdens. But as the Eurozone debt crisis demonstrated, such imbalances are unhealthy and risk precipitating a financial meltdown should the world’s creditors ever pull the plug. The Fed’s enormous monetary expansions in the wake of the 2007-08 financial crisis raised the risks even further by piquing fears of inflation and dollar debasement.

But what is to be done? It would seem that no major change to the current status quo is in the offing. The fact that certain countries have been able to accrue trillions of dollars of debt with no obvious exchange rate repercussions implies that classical economic models matter less than they once did. Nevertheless, it is worth considering the line-up of possible alternatives to the prevailing dollar hegemony, namely special drawing rights, virtual currencies, multiple reserve currencies and gold.

Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) are IMF-controlled world money whose value is calculated using a basket of currencies. They were first introduced in 1969 to reduce the world’s reliance on the dollar for international liquidity but fell by the wayside until the late financial crisis. Since then, nations have been maintaining an increasing share of their reserves in SDRs and have using them to settle their trade accounts. However, their utility has been somewhat hampered by the fact that individuals and corporations cannot use them and there are no liquid assets denominated in SDRs.

Virtual currencies such as bitcoin have also been touted as an alternative to the dollar. Introduced in 2011, bitcoin is intended to be a digital analogue to gold: a universal money that could be owned by everyone and spent anywhere. It was designed to be scarce – only 21m would ever be released – and hard to counterfeit, protected by uncrackable digital keys. Unlike traditional currencies, there was no central issuing authority – bitcoin was created and sustained by its users, connected by software protocol. Exploiting the post-financial crisis zeitgeist, it promised to give power to the people but after numerous scandals such as its association with the Silk Road website used for selling vice anonymously, the loss of $400m from a client’s account and its creator’s disappearance, its fortunes receded somewhat but came back with a vengeance in 2016. The growing commercial interest in its underlying blockchain methodology and a surge in demand from China, made it the best performing currency of 2016.

Another scenario is the rise of multiple reserve currencies, with no single dominant currency. According to this thesis, there would be a gradual move from King Dollar to the euro, rouble, real and yuan. There are precedents for this such as the simultaneous circulation of the pound and dollar in the early 20th century and the florin and Venetian ducat in the 16th century. But there is no history of simultaneous reserve currencies being used without a single systemic anchor such as gold. Instead of just the Fed over-issuing its currency, several central banks would be invited to do so at once, in which case there would be no safe-harbour reserve currency. Moreover, regional currency blocs could easily devolve into regional trade blocs such as that which emerged around the pound during the early 20th century: the so-called sterling area.

A more intriguing possibility is the return to gold – a notion which has received support at the highest levels. Donald Trump tweeted his support for gold during his presidential campaign and Alan Greenspan and the former World Bank President Robert Zoellick made similar noises. The Fed’s gargantuan monetary expansions after the financial crisis and fears that debtor governments may seek to inflate away their obligations have led some to fondly reminisce about the merits of the gold standard or a gold-exchange standard such as that effigiated by Bretton Woods. So let’s examine these two systems in turn.

Classical Gold Standard (1870-1914)

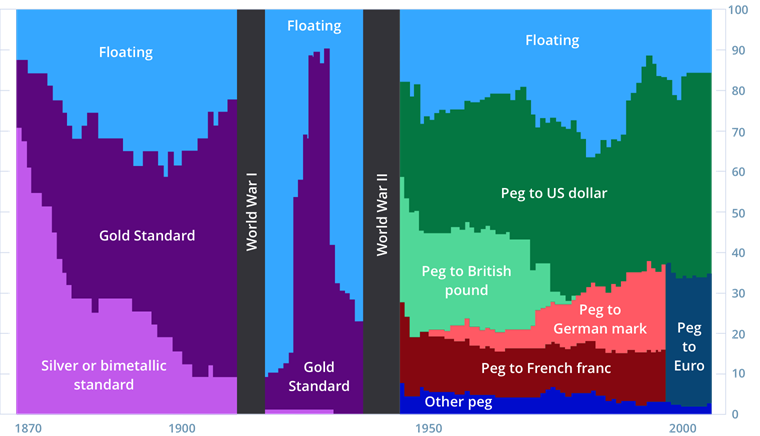

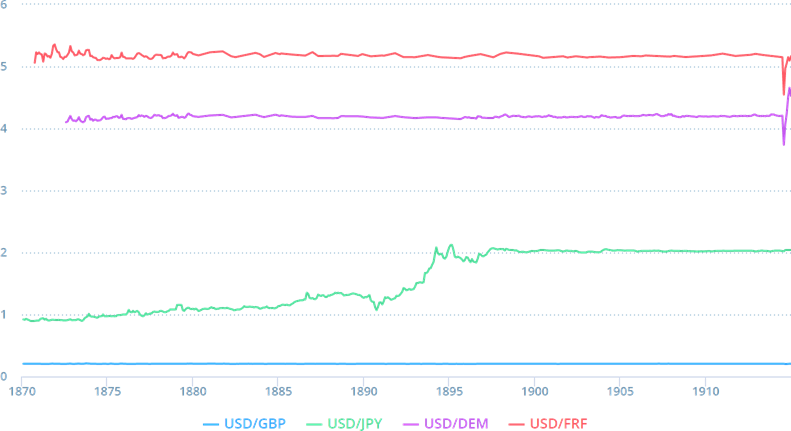

Until the 1870s, most monetary systems were based on a bimetallic standard. Only Britain was on the gold standard, after Sir Isaac Newton in his capacity as Master of the Mint, set the wrong gold-silver price ratio in 1717 and drove silver out of circulation. But by 1870 Britain had become the world’s preeminent commercial power, creating an incentive for her trading partners to adopt her mono-metallic standard. After Germany went onto gold in 1871 and the US in 1873, the preponderance of the world’s industrial countries followed suit, such that by 1900 only China and a few Central American countries remained on silver.

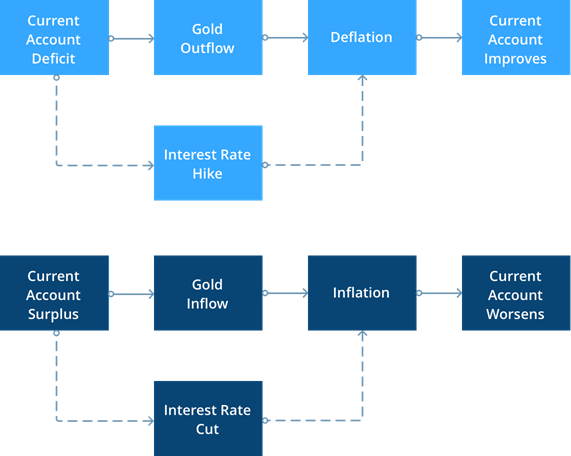

The gold standard ensured stable exchange rates by fixing them in terms of gold. Central banks were willing to convert paper currency for a specified amount gold. The corollary of this was that countries could not run persistent trade imbalances. When a country ran a trade deficit, it experienced a gold outflow, initiating a self-correcting chain of events known as the price-specie flow mechanism. With less gold-backed money circulating internally, prices fell in the deficit country, making imports more expensive and exports cheaper and thus eliminating the deficit. But in practice, external adjustments typically took place in the absence of substantial movements of gold. When a country ran a deficit, its central bank could intervene to accelerate the adjustment of the money supply by adjusting its discount rate. If the bank raised the rate to make discounting more expensive, fewer intermediaries would be inclined to present bills for discount to obtain cash from the central bank. This would decrease the volume of domestic credit and restore the balance of payments equilibrium without requiring gold flows.

The lynchpin of the classical gold standard was the priority attached by governments to maintaining convertibility. Political pressures to subordinate currency stability to other objectives such as growth and full employment were not a feature of the pre-1914 world – wages and prices were flexible, allowing a balance of payments shock to be accommodated by a fall in costs and wages. Investors were aware of these priorities so did not fear devaluation prior to 1914 and when currency fluctuations did occur, investors reacted in a stabilising fashion. If the exchange rate fell to the point where gold arbitrage would become profitable, funds would flow in from abroad in anticipation of the profits that would be made by investors in domestic assets when the central bank intervened to strengthen the exchange rate.

The gold standard had two major advantages. First, it provided long-run price stability since it obliged governments to commit to time-consistent monetary and fiscal policies. Governments could not autonomously adjust their money supply without suffering debilitating gold flows. That is why Sir Winston Churchill considered it “knave-proof”. Second, the gold standard era was marked by low interest rates since bond markets regarded the gold standard as a “Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval”. Currencies tethered to gold were unlikely to be debased and their governments were unlikely to engage in reckless fiscal policy so it was relatively safe to lend and invest money in countries that were on gold. For these reasons, the gold standard was associated with a spectacular increase in world trade.

However, not all was rosy in the garden. The corollary of the monetary authorities’ commitment to maintaining stable exchange rates was that they could not pay much attention to unemployment and growth. Moreover, pegging the international monetary system to a scarce metal placed a real constraint on the growth of credit. Indeed, the gold standard frequently generated deflation since world growth often outstripped the availability of gold for monetary uses. This was particularly the case before the invention of the cyanide extraction process and the major gold discoveries in Klondike and South Africa in the late 1890s. Agricultural commodities such as wheat experienced secular price declines during the gold standard era, causing major hardship to farmers. Another disadvantage was that the gold standard had the capacity to readily transmit crises around the world, courtesy of the aforesaid price-specie flow mechanism. The panics of 1857, 1973, 1907 and 1929 emanated from the US but ended up dragging down much of the rest of world.

The Demise of the Gold Standard (1914-1930s)

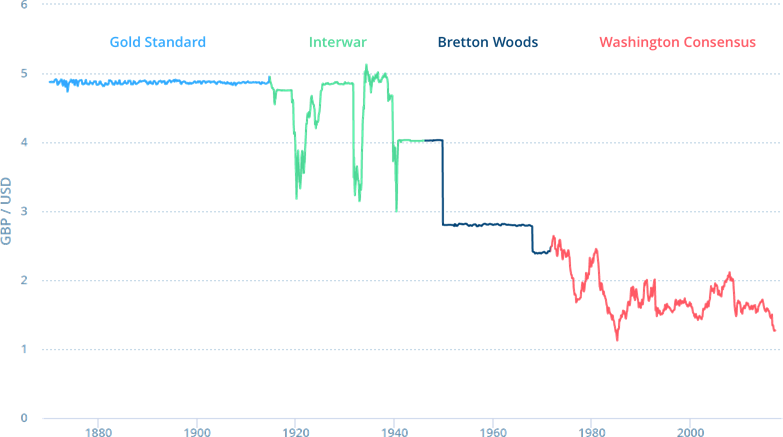

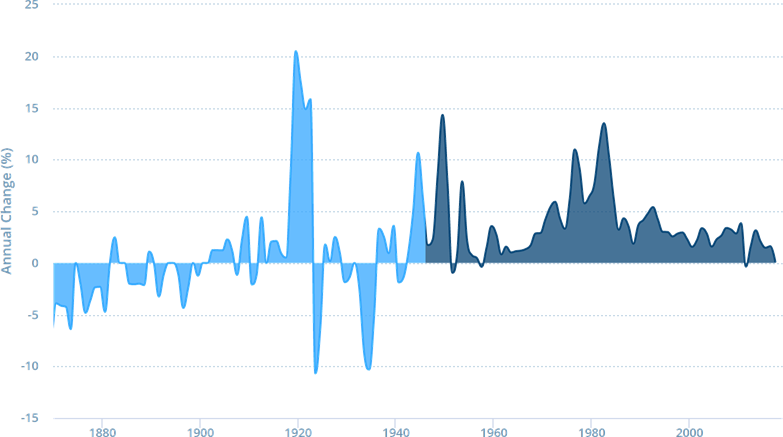

The Classical Gold Standard ended abruptly in 1914 with the outbreak of WWI. Private trade and gold exports were suspended and individual countries began financing their war debts by issuing bonds and printing money, resulting in differing interest rates. After the war, the major countries attempted to restore the gold standard but with disastrous consequences. Britain’s decision to return to gold at the pre-war parity in 1925, motivated by a sense of duty to Britain’s creditors, left the pound 10% overvalued against the dollar due to the inflation gap since 1914. France, meanwhile, not feeling any such compunction, joined at a lower parity, allowing it to steal trade from under the noses of its rivals.

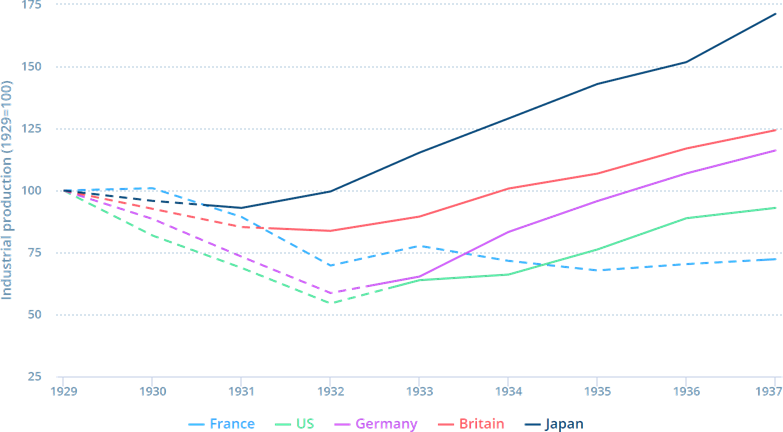

In 1931, Britain abandoned the gold standard again, followed by most other countries, resulting in an immediate return to growth. The US grimly clung on, though reduced the gold value of the dollar from $20/oz to $35/oz in 1933. These measures freed the world’s currencies from their golden fetters but the damage had already been done – the failure to accommodate the fall-out from the 1929 Wall Street Crash encouraged the rise of protectionism and trading blocs, to the detriment of world trade and growth.

Bretton Woods (1945-1971)

A new monetary order emerged from the agreement at Bretton Woods at the end of WWII to prevent nations from engaging in the currency and trade wars that had so damaged the world economy in the 1930s. This involved the creation of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (the forebear of the WTO), and the international gold-exchange standard.

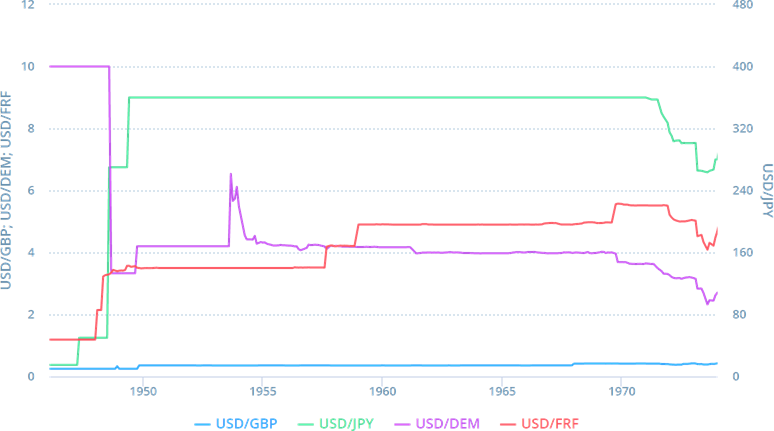

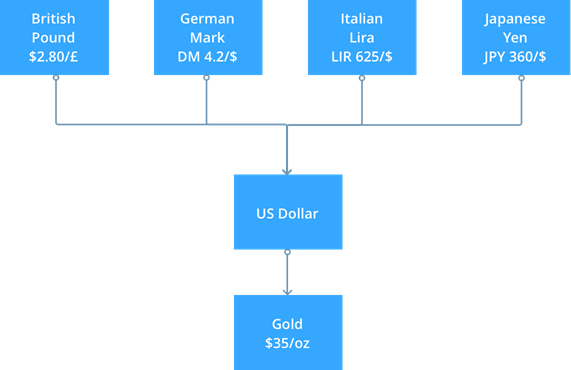

Under Bretton Woods, countries pegged their currencies to the dollar at specified parities, which in turn was convertible into gold at the official rate of $35/oz. However this only applied to dollars held by central banks and governments and not by private citizens. The US provided price stability but did not engage in currency intervention – other countries had to intervene to fix their exchange rates against the dollar. These pegs were intended to be adjustable if “fundamental disequilibria” occurred, and were accompanied by tight capital controls that were designed to prevent speculative attacks and afford central banks a modicum of policy independence. In the event that any balance of payments problems arose, the IMF stood ready to extend credits to the affected nation(s). In sum, the system was intended to marry flexibility and stability, overcoming the inadequacies of the Classical Gold Standard.

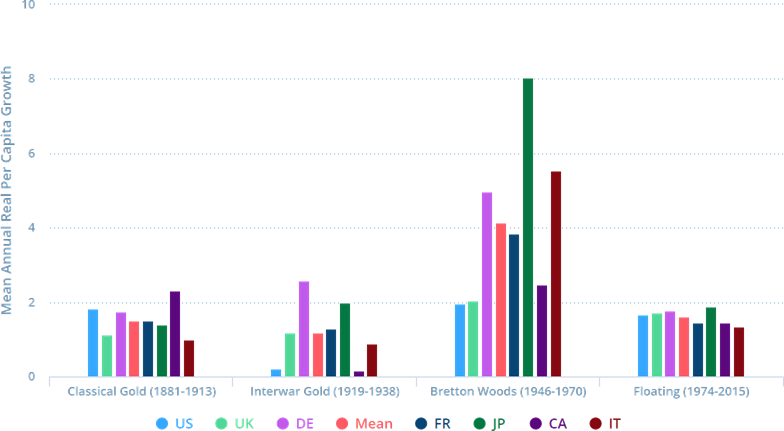

There are mixed views on the record of Bretton Woods. For some, it was an important component of the post-war golden age of growth, delivering exchange rate stability, in marked contrast to the preceding and subsequent volatility. It dissipated payments problems, allowing the phenomenal expansion of international trade and investment that fuelled the 1950s and 1960s worldwide boom. Others contend that Bretton Woods was a consequence rather than a cause of the post-war growth and suffered from a number of structural weaknesses that sealed its fate from the outset. The wonder, they contend, is that it managed to survive so long. So what were these weaknesses?

First, there was no automatic mechanism for dealing with current account imbalances. Unlike the gold standard, European nations could no longer resolve balance of payments problems by adjusting interest rates or adjusting domestic prices. Governments could no longer subordinate growth and full employment to exchange rate stability. Exchange controls and import restrictions such as those employed by European nations during the early years of Bretton Woods, ceased to be an option after the restoration of current account convertibility in 1958 and the development of Eurodollars in the 1960s. This only left parity adjustments for removing disequilibrium which nations refused to do for fear of embarrassment – parity adjustments were a conspicuous sign of failure.

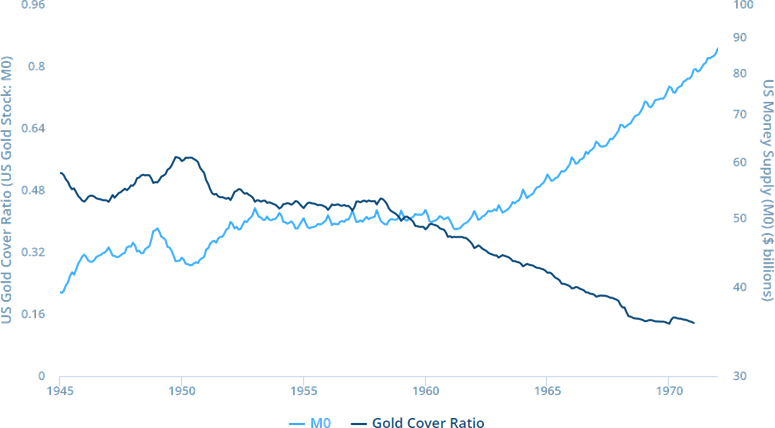

Second, the centrality of the dollar to the system posed a number of problems. It was natural for central banks to supplement their gold reserves with the dollar, given the US’s dominant position in trade and finance and its large gold stock. However, this permitted the US to run chronic trade deficits, allowing Americans to live beyond their means and put off attempts to strengthen their current account. Many nations bristled at this ‘exorbitant privilege’ and De Gaulle even threatened to liquidate France’s dollar balances. A related problem was the Triffin dilemma. Confidence in the dollar was based on the perception that the US would convert it into gold. Therein lay a paradox. World trade depended on the ready supply of dollars but providing these dollars would reduce the US’s credibility to convert all of them into gold. This became a real problem after 1960 when the world’s dollar balances exceeded US gold reserves at the ordained rate of $35/oz.

Third, Bretton Woods was highly reliant on foreign support for the dollar. International cooperation was possible during the early years when the dollar provided price stability, but was less forthcoming when the US began inflating in the 1960s due to deficit spending on the Vietnam War and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society initiative. Inflation-averse countries such as Germany were loath to import US inflation. An example of the necessity for international cooperation is furnished by the London Gold Pool. In 1961, a number of European central banks pledged not to convert their dollars and sold gold from their reserves to relieve speculative pressure on the dollar. But when it later became clear that the US would not subordinate its economic and political objectives to defend the dollar price of gold, the Pool unravelled in 1968 under heavy speculative pressure. To prevent the Fed from being completely drained of gold, a two-tier gold market was instituted, whereby private gold prices could rise but the price for official transactions remained unchanged. When the private market price immediately rose to $40, there was a strong incentive for foreign central banks to cash in their dollars at the original rate of $35/oz.

The Demise of Bretton Woods (1971-73)

Eventually, in spring 1971, large defections from the dollar to the deutschmark prompted Germany to suspend intervention and allow the mark to float upwards. Once the dollar flight had started, it couldn’t be contained and by mid-August it was reported that France and Britain intended to convert dollars to gold. On 13 August, President Nixon closed the Fed’s gold window, suspending the commitment to provide gold to foreign central banks at $35/oz or any other rate. He also introduced a 10% import surcharge to coerce other countries into revaluing their currencies, so as to avoid the ignominy of devaluing the dollar. Together, these actions are known as the Nixon Shock.

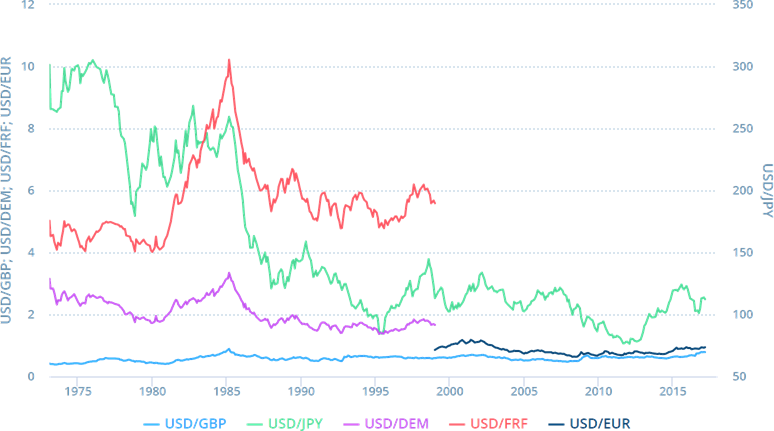

Over the following four months, the world’s major nations engaged in negotiations over the reform of the international monetary system, culminating in the Smithsonian Agreement in December. It was agreed that dollar devaluation would be limited to 8% with the rest of the change in relative prices provided by revaluing the yen, Swiss franc and deutschmark. Bretton Woods’ currency fluctuation bands were widened from 1% to 2.25% and the US import surcharge was abolished but the US was not obliged to reopen its gold window. In reality, little had changed. US policy remained too expansionary to be consonant with pegging the dollar to foreign currencies and having devalued once, there was no reason to suppose the dollar wouldn’t be devalued again. A speculative attack on the sterling forced Britain to float out of its band in 1972, followed by Switzerland in early 1973 and when the dollar was devalued by 10% against the major European currencies in February, dollar flight resumed perforce. Things reached a head in March when the deutschmark and the other EEC currencies floated upwards, delivering the final coup de grace to Bretton Woods.

Washington Consensus (1973 – Present)

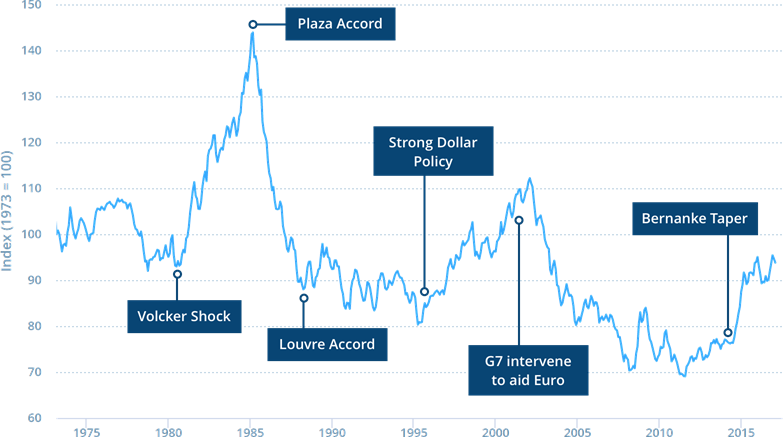

After the collapse of the Smithsonian Agreement, the major currencies of North America, Europe and Japan floated. During the 1970s, the dollar depreciated as inflation bit and then commenced its dramatic ascent following the 1979-80 Volcker Shock when US interest rates were hiked to unprecedented levels. By 1985, the dollar’s strength was harming US competitiveness, prompting the US, Japan, Germany, France to sign the Plaza Accord, under which they jointly intervened to lower the dollar. Their intervention was so effective that they had to sign another agreement in 1987 - the Louvre Accord - to stop the further fall of the dollar. Prior to these meetings, free floating exchange rates were considered the best but thereafter, the major countries began to cooperate more.

The main tenets of the Plaza-Louvre Accord, which still persists today, are:

- Unannounced, soft target zones for the major currencies. Ordinarily the market is left to decide exchange rates but when rates move out of the target zones, there should be joint intervention.

- Interventions must be sterilised (i.e. central banks must soak up the inflows with bonds) such that the they do not affect the domestic money supply.

- Capital mobility must be preserved.

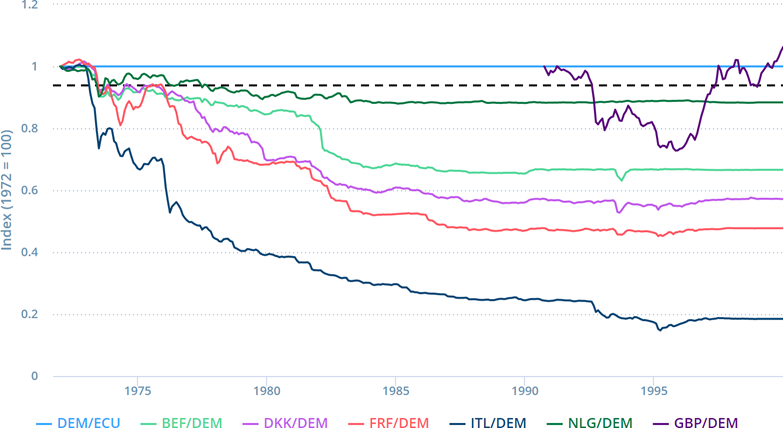

The Evolution of the Euro (1972-Present)

Seeking exchange rate stability in the wake of the Nixon Shock, Germany and several other European nations created a new system in 1972 dubbed the “Snake in the Tunnel”, under which their currencies were kept within +/- 2.25% of each other and a band of 4.5% against the dollar. It didn’t live up to expectations however, with frequent realignments and a couple of wholesale withdrawals. Essentially, there was a tug of war between Germany which favoured low inflation and other countries such as France which sought to expand. In the absence of an overarching monetary/fiscal authority, strong-currency countries such as Germany couldn’t be certain that weak-currency countries would undertake the necessary policy adjustments to maintain their pegs, so were loath to intervene on their behalf.

The European Monetary System (EMS) was created by France and Germany in 1979 to resolve these deficiencies. Participating currencies were still held within their bilateral margins of +/- 2.25% but were now accompanied by capital controls to allow a degree of monetary policy autonomy. More importantly, a new entity - the European Monetary Fund - was established to provide credits known as ecus to members experiencing balance of payment problems. In practice, the EMS was a Deutschmark-centred system with German monetary policy serving as the nominal anchor – other countries reduced their inflation towards Germany’s which was the lowest in Europe. This time none of participants had to withdraw and a far greater degree of exchange rate stability was achieved, particularly after 1985.

In 1991, the EMS members were full of optimism. The EMS had proven resilient to the collapse of the USSR and German reunification. In this spirit, they set out their commitment to monetary union under the Maastricht Treaty, agreeing that by 1999 they would:

- hold their currency within the EMS band for at least two years

- run an inflation rate over the preceding year that did not exceed that of the three lowest inflation member states by more than 1.5%

- reduce their public debt as a percentage of GDP and GDP growth to 60% and 3%, respectively

- maintain a nominal long-term interest rate in the preceding year that did not exceed 2% of the three most price-stable members

Yet the following year, the EMS faced its severest test. In mid-September, Britain crashed through its EMS limit and ignominiously withdrew from the system, less than two years after joining. Italy likewise fell through its band and was forced to float but somehow remained part of the system. Most other EMS currencies came under speculative pressure and were forced to realign. Essentially the crisis stemmed from the inability of European governments to raise interest rates in the face of grinding recession but speculative attacks such as that of George Soros’s on the pound also played a role, creating self-fulfilling crises in otherwise solvent national economies.

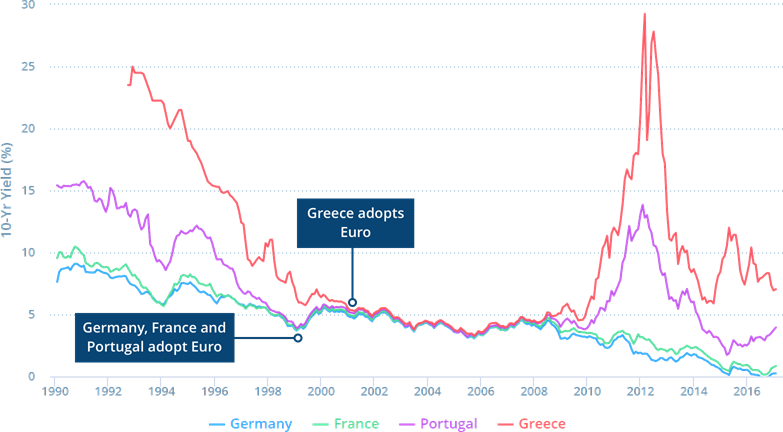

Following the early 1990s crisis, the situation improved – with expansion in Europe, austerity became easier to implement and the absence of laggards such as Britain removed a drag. EMS members locked in their exchange rates in 1999 and the euro was introduced in 2002. The euro brought numerous benefits such as fewer disruptions to intra-European trade, improved price transparency, and a reduced cost of capital for European firms. Yet there were several structural weaknesses with which we are now well acquainted. Adapting to a single monetary policy wasn’t easy. Slow-growing economies such as Italy preferred looser European Central Bank (ECB) policy and a weaker euro whilst fast growing economies such as Ireland preferred tighter policy to cool down their overheated economies. Moreover, the interest rates of “convergence economies” – EU slang for poor, peripheral economies such as Greece and Portugal - suddenly fell to German levels. Consumption and investment surged, and wages were pushed up dramatically. After their booms, convergence economies were saddled with excessive wages, lagging competitiveness and increasing unemployment, necessitating painful austerity measures.

Bretton Woods II (2000 - Present)

At the turn of the millennium a new system was emerging, dubbed Bretton Woods II. A savings glut in the Middle East and the Far East was superimposed on a US savings drought, resulting in chronic US current account deficits.

From the late 1990s, China grew at a phenomenal rate, fuelled by investment of over 40% of GDP. National saving was even higher at 50% of GDP. Middle Eastern oil exporters and other ASEAN countries also had savings gluts. The US meanwhile was in the throes of the dot com boom, with investment levels exceeding national savings. The disparity between national investment and savings grew still further when President Bush’s tax cuts reduced US government savings.

Accordingly, foreign governments parked their excess savings in US assets, chiefly treasuries. This status quo was tolerated by both sides for different reasons. Asian export-orientated economies such as China were keen to accumulate dollar reserves to smooth international payments and boost the competitiveness of their manufactured exports by holding down their currencies against the dollar. The US on the other hand was able to service its debt more cheaply than would otherwise be the case and its residents were able to live beyond their means, courtesy of the world’s developing nations. These global imbalances were christened Bretton Woods II in homage the Bretton Woods era when Europe and Japan ran net surpluses against the US.

By 2005, the US changed its stance, blaming China and its neighbours for harming its domestic manufacturers and for not letting their currencies rise. To forestall trade sanctions, China began letting the renminbi appreciate but only to a fraction of what was required to restore balance globally. Understandably, it did not want to mess with economic success. China feared that suspending its currency peg might trigger a dollar crash, harming global growth and causing it to suffer a loss on the value of its dollar reserves.

The Impossible Triangle

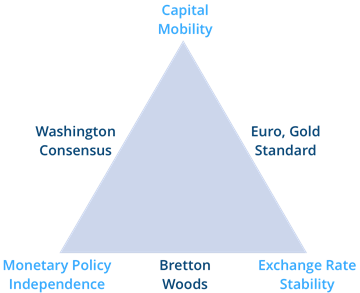

When it comes to the modern international monetary system, the Rolling Stones’ aphorism “You can’t always get what you want” rings true. You want exchange rate stability, capital mobility and monetary independence but can only ever achieve two of these at any given time. As we’ve seen, the Gold Standard and Euro combined capital mobility and currency stability but sacrificed monetary independence. Conversely, Bretton Woods married stable exchange rates with central bank autonomy but imposed capital controls so stringent that some travellers resorted to smuggling cash in hollowed loaves. The Washington Consensus, meanwhile, has been marked by free capital flows and monetary policy autonomy but exchange rate instability.

Even allowing for the abovementioned trilemma, the current state of the international monetary system leaves a lot to be desired. Chronic imbalances and the potential for long-term dollar devaluation cause considerable anguish to policymakers. Nevertheless, a grand redesign along the lines of Bretton Woods is not likely to be imminent. The world has a great deal invested in the current monetary status quo and there is no clear consensus on how the current system might be replaced. Historically, it has taken a major upheaval such as a world war or the prospect of an immediate national bankruptcy to effect a transition, and it is not clear that the late financial crisis constituted enough of a jolt. However, as witnessed during the twilight years of Bretton Woods, there comes a point where nations take matters into their own hands; where their vested interest in not rocking the boat is surpassed by their desire to escape a sinking boat. The nations of the Arabian Gulf have been mooting a return to a gold-based currency in recent years and it is perhaps significant that the central banks of Russia and China have been steadily accumulating gold. And where governments fear to tread, private citizens have been busily establishing their own monetary system courtesy of bitcoin.

In our next article, we shall consider what came before the modern international monetary system - a journey which will take us from the money markets of Assyria and Babylon to the demise of bimetallism.