18 September 2018 | 4 min read

Railway Mania

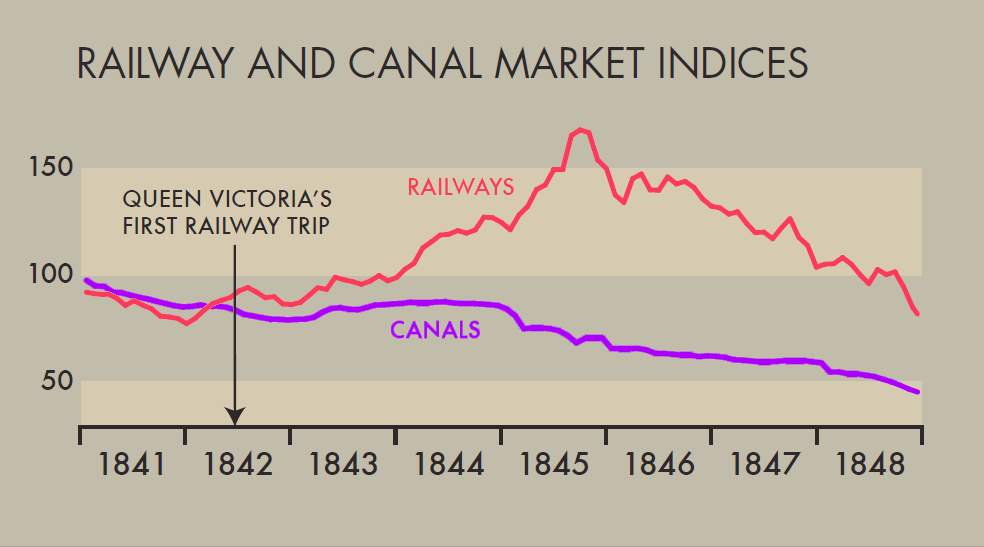

Steam trains, still a new phenomenon, seized the English public’s imagination in 1842 following Queen Victoria’s first railway trip. With investment decisions decoupling from reality, however, the boom soon became a runaway train which slammed into the buffers in October 1845.

The country is an asylum of railway lunatics

Wordsworth

Getting a Full Head of Steam

When steam engines first appeared in the 1820s, they were met with widespread hostility. It was feared that they would prevent hens from laying eggs and cattle from grazing, that their noxious fumes would blacken the fleeces of sheep, and that passengers travelling at breakneck speeds of 12.5 mph would be atomised. Landowners were also concerned that locomotives would shatter the tranquillity of their estates and injure land values.

Notwithstanding such apprehensions, there were two early speculative flurries: the first following the establishment of the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825, and the second after the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway six years later.

Yet both of these were fairly short lived and by the late 1830s, with 2,000 miles of track in place, many felt the national network was complete. Journey times from London to Glasgow had been reduced to 24 hours, prompting the Railway Times to ask: ‘What more could any reasonable man want?’

By the early 1840s, speculative interest in the railways was beginning to pick up again. Much of the earlier opposition had diminished and most could now see the benefits of steam travel compared to other modes of transport, and when Queen Victoria made her first train trip in 1842 railways became quite the rage.

Investors fawned upon railway companies, lured by their plummy dividends, and commonly believed they would be ‘safe in midst of panic’, encouraging promoters to rush through plans for new lines and issue new scrip. Share subscriptions sold instantly and commanded huge premiums, even for the most dubious projects.

Railway schemes were typically projected in the following way. Advertisements for a new company would flood the newspapers, including a list of ‘committeemen’ (company trustees) and the promise of a 10% dividend. If the subscription went well, the committeemen would retain a large share allocation, creating a scarcity, and then get their friends in the railway press to ‘puff’ the stock, whereupon they would sell it at a premium.

Although the committeemen were wont to be billed as upstanding members of the local community, they were often, according to The Times, ‘the most notorious scamps, alias swindlers’, whose sole interest was personal gain. Many politicians were also in on the game, acting as committeemen and hawking their parliamentary votes in return for shares.

Emergency Announcements

Some public figures, notably Alexander Baring and William Gladstone, urged caution and called for tighter regulation but their appeals fell upon deaf ears – hardly surprising, given that most MPs were in on the game. Prime Minister Peel refused to intervene, believing that the previous year’s Bank Act (which stipulated that notes must be fully convertible) had prevented all undue speculation.

Speculation had reached fever pitch by summer 1845. By June there were twelve schemes coming before Parliament each week and plans for over 8,000 miles of new track. The whole country was consumed with railway mania, and heaving with ‘railway hotels, office-houses, lodging-houses, boarding-houses; railway plans, maps, views, wrappers, bottles, sandwich-boxes, and timetables…’, as Charles Dickens observed in Dombey and Son.

Speculative fervour pervaded all sections of society and blurred class divides. ‘Men who were known to have been penniless a year before, suddenly kept their broughams or started barouches. Valuable diamonds gleamed from fingers which had hitherto been guiltless of the bright adornment.’ Female speculators also became a common sight, ‘Duchesses’ delicate fingers handled scrip; old maids inquired with trembling eagerness the price of stocks; young ladies’ eyes ceased to scan the marriage list – deserting this for the table of shares, and startling their lovers with questions respecting the operations of bulls and bears.’

Running Out of Steam

As the summer wore on, the railways began to lose their gloss. It was becoming increasingly clear that many had speculated beyond their means and were in no position to meet the capital calls that were now being made. For example, a parliamentary report found that two brothers who had subscribed for £37,500 of stock were the ‘sons of a charwoman living in a garret off a guinea a week’.

There was also growing evidence of fraud, lovingly exposed by The Economist and The Times. Both publications, despite carrying dozens of railway advertisements, began to launch blistering tirades against the railway companies and the cynicism of their investors. A letter in The Times stated,

‘There is not a single dabbler in scrip who does not steadfastly believe – first, that a crash sooner or later, is inevitable; and secondly, that he himself will escape it… No-one fancies that the last mail train from Panic station will leave him behind.’

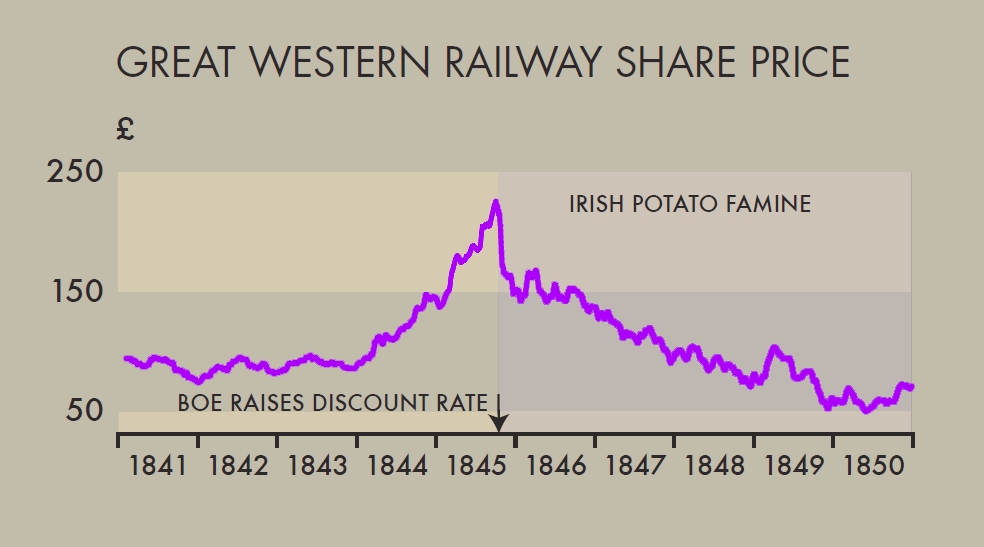

By early October, shares were beginning to decline as investors were forced to liquidate stock to meet the calls; on 14 October, a failed speculator shot himself in Hyde Park, crystallising investors’ apprehensions. To cap it all came the news of the Irish potato blight. So when the Bank of England raised interest rates by 0.5% a few days later, share premiums evaporated and there was an ‘avalanche’ in prices, with the shares of the Great Western – Britain’s largest operator – ‘down 40% from their August peak’.

Summing up the débâcle, The Times triumphantly exclaimed: ‘The dismal mockery of intelligence and discretion serves only to reveal the inward void. A mighty bubble of wealth is blown before our eyes, as transient, as contradictory to the laws of solid material, as confuted by every circumstance of our actual condition, as any other bubble which man or child ever blew before.’

The Big Swollen Gambler

George Hudson, the corpulent chairman of the York & North Midland, became the icon of the railway mania, controlling over 1,000 miles of railway by 1844. Hudson first became involved in railways when he met George Stephenson and persuaded him to turn York into a railway hub. After joining the York & North Midland in 1842, he started to build a huge empire through a series of mergers. His management style was characterised by a combination of ostentation, penny pinching, rule bending and bullying. He charged the highest tariffs but kept tight control of costs – several fatalities can be attributed to this. Hudson misled investors by paying generous dividends (and his ‘expenses’) from the company’s capital and keeping the accounts secret. Investors did not feel the need to probe too deeply in the fat years but after the bubble burst, Hudson’s fraudulent behaviour came to light. Publicly shamed, he fl ed to the Continent and died a poor man.

Off the Rails

Britain’s railway investors reaped a bitter crop that autumn, not unlike Ireland’s potato farmers: ‘The affected potato assumes a dark hue, and by that same token of his blue look may the scripholder be distinguished. The potato, again, it is recommended should be taken to the mill and ground. The unfortunate speculator, in like manner, finds that… he has brought his nose to the grindstone… On one hand, we hear of potatoes being thrown to the cattle; on the other, we have rumours of speculators having “gone all to the dogs”.’

Given the crushing burden of the continued share calls, the government passed a dissolution act allowing railway companies to be dissolved if at least three-quarters of shareholders agreed. Yet despite the act, declining share prices and growing disillusionment, railway building continued, though this was mostly based on schemes which had been launched before the October crash.

By summer 1846, bankruptcies were at an all time high and Britain was mired in economic gloom, with middle-class families in particular suffering: ‘No other panic was ever so fatal to the middle class. It reached every hearth, saddened every heart in the metropolis.

Entire families were ruined. There was scarcely an important town in England but what beheld some wretched suicide. Daughters delicately nurtured went out to seek their bread. Sons were recalled from academies. Households were separated: homes were desecrated by the emissaries of the law.’

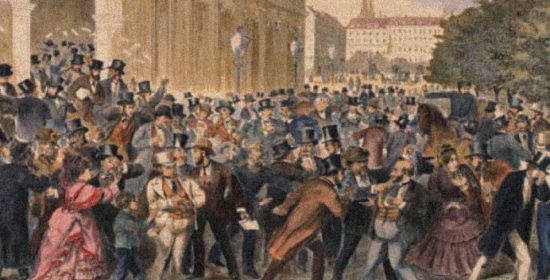

Vienna's Railway Mania

Railway Mania was by no means confined to Britain; in Austria in 1837 it took on an even more dramatic form. ‘In Austria, the people are almost mad on the subject of railroads. At a meeting held in Vienna, the place being found too small for the crowd, which was estimated at 30,000 at least, Prince Swartzenburg granted the use of his palace. Still the pressure was so great that the doors were forced in, walls scaled, limbs broken, and even bloodshed. The efforts of a battalion of grenadiers, a detachment of light horse, and 200 police officers, were insufficient to keep the crowd back, and with the flats of their swords produced no effect. – Several of the military were also hurt.’

Panic Stations

By early October 1847, the Bank of England’s bullion reserves had fallen to dangerously low levels, reaching crisis point on Monday 17 October, when there was a sharp fall in Consols as everybody sought refuge in gold.

The following day, four major banks failed and by the end of the so-called ‘week of terror’, the Bank of England had such low reserves that another run would have been fatal. On Saturday 23 October, a group of prominent financiers visited Downing Street and entreated the Prime Minister to suspend the Bank Act (i.e. the full convertibility of banknotes) which was causing such misery in the City. Two days later, their request was granted and the crisis rapidly dissipated.

The railway mania was not entirely negative. As well as Britain being left with a first rate transport system, the high amount of railroad construction (1844–47) provided employment for hundreds of thousands of Irish navvies during the potato blight, representing a transfer of capital from middle-class investors to the needy.